This week we have the honor of meeting Marco Leona from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and share his incredible story and talent.

To wind up at the Metropolitan Museum of Art must have been an interesting journey. Could you please tell us a little about yourself and the journey that brought you there.

I’m a chemist. I studied chemistry in Italy and then crystallography which is the discipline that studies crystalline materials particularly minerals; I obtained my PhD in Italy. Then I came to the US for a postdoctoral period at the University of Michigan continuing along that line with regular chemistry. That’s where I started looking for an alternative career in the industry.

Simultaneously, I discovered American art museums and found that they are very interesting and different than European museums, especially the Italian ones.

There is a degree of integration among different professions and also a broader array of professions within the museum. I discovered that there were scientists working in museums. Here in the US I found they have science labs that we are supporting the restorers, conservators and the art curators in their investigation which was a big discovery for me. Very few people were hiring scientists in museums and it was just a few university laboratories doing this and there were no scientists in museums, and even now there are no scientists in museums in Italy.

So I always had the thought to do this but I always left it as a thought thinking it would be nice but I can’t.

I discovered this field, then I just picked up the phone and started calling all the labs in museums. I spoke with their scientists and asked about an opening. I had a list of 12 it names to call. I still remember in fact my wife Jennifer, who at the time I was dating, said who told me that since I had a list of contacts to just pick up the phone and call.

And I wondered how to do that because I wouldn’t do that in Italy. She reminded me that this is not Italy and this is how you do things in America. So I just called them.

Everybody was very nice. There weren’t many opportunities. But the last person I called was the scientist at Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He said yes and he informed me that they had a fellowship I should apply for and so I applied. I actually went there on my own. I took a Southwest flight that probably stopped in 16 places before getting to LA to go for the interview.

They offered me a job that paid very little. I could manage and so, after a lot of trouble to get the Visa permit, I started in LA. I still remember when I went there for my interview because it was March and there was still snow on the ground in Ann Arbor, Michigan where I was living at the time. I got to LAX (which is not the best place in LA) but when I saw the palm trees I said, I’m going to get this job. So I started it and that September I moved to LA. I spent two years there as a fellow which is basically a very Junior position but it was an extraordinary experience because I really had a fantastic mentor, great colleagues, and it was really so integrated. There I got to work on everything from paintings to ancient Egyptian silver and bronze sculptures, Modern art. So really that was how I learned. After two years, I had the opportunity to get a research position at the Freer Gallery in Washington DC, which is the collection of Asian art of the Smithsonian. There I started working on a special project on Japanese art.

Then, after two years LA County Museum of Art called me and told me that the person I worked with there had retired and asked if I was interested in the job of senior scientist there. After some time there the Met museum called. Even though I loved Los Angeles, I could not say no to New York. New York is where things happen and and my task at the MET was really to create the first scientific research department in the all history of the MET. The MET had a few scientists, but they were working on different conservation areas, in different environments. So they asked me to come in, bring them together and create a bigger structure. Therefore, I gave up surfing in the morning before I went to work and I moved to NYC.

I’m still here, 16 years later.

You are a very successful scientist, what is your role/job description at the Met museum?

Now every day the first thing I do is to arrange the calendar for the following week because out of 16 people on my team I can only bring in six people every day because of Covid-19 occupancy restrictions, so I’m just like the guy who takes down bookings for the tennis courts or something like that. It’s not very exciting and you can imagine everybody wants to be here. A lot of my work is administrative. I created a team, I assembled a work structure; as a non profit we have to do a lot of fundraising that is looking for grants to secure positions to take care of the maintenance of equipment and to purchase new equipment. My biggest priority right now is really helping museums and the Arts to achieve more representation and more diversity.

We’re lucky that in the sciences we have an amazing pool of talented scientists of color, so we can take advantage of programs that existed in the past. We increased the minority representation in the sciences and our task now is reaching out to these candidates letting them know that this is a great career and they can join the museum and contribute and help us become more representative of America. To do that I just need to do a lot of knocking on doors to get money.

Because today is a very quiet day I could come in to do the interview with you and also work in the laboratory. I’m thinking it’s a luxury for me. I can shut off the paperwork and go to the laboratory where I’m putting together a new instrument that will allow us to do more work in identifying materials in works of art. Tomorrow I have a new Junior scientist who’s a PhD candidate here at City College and who works with me.

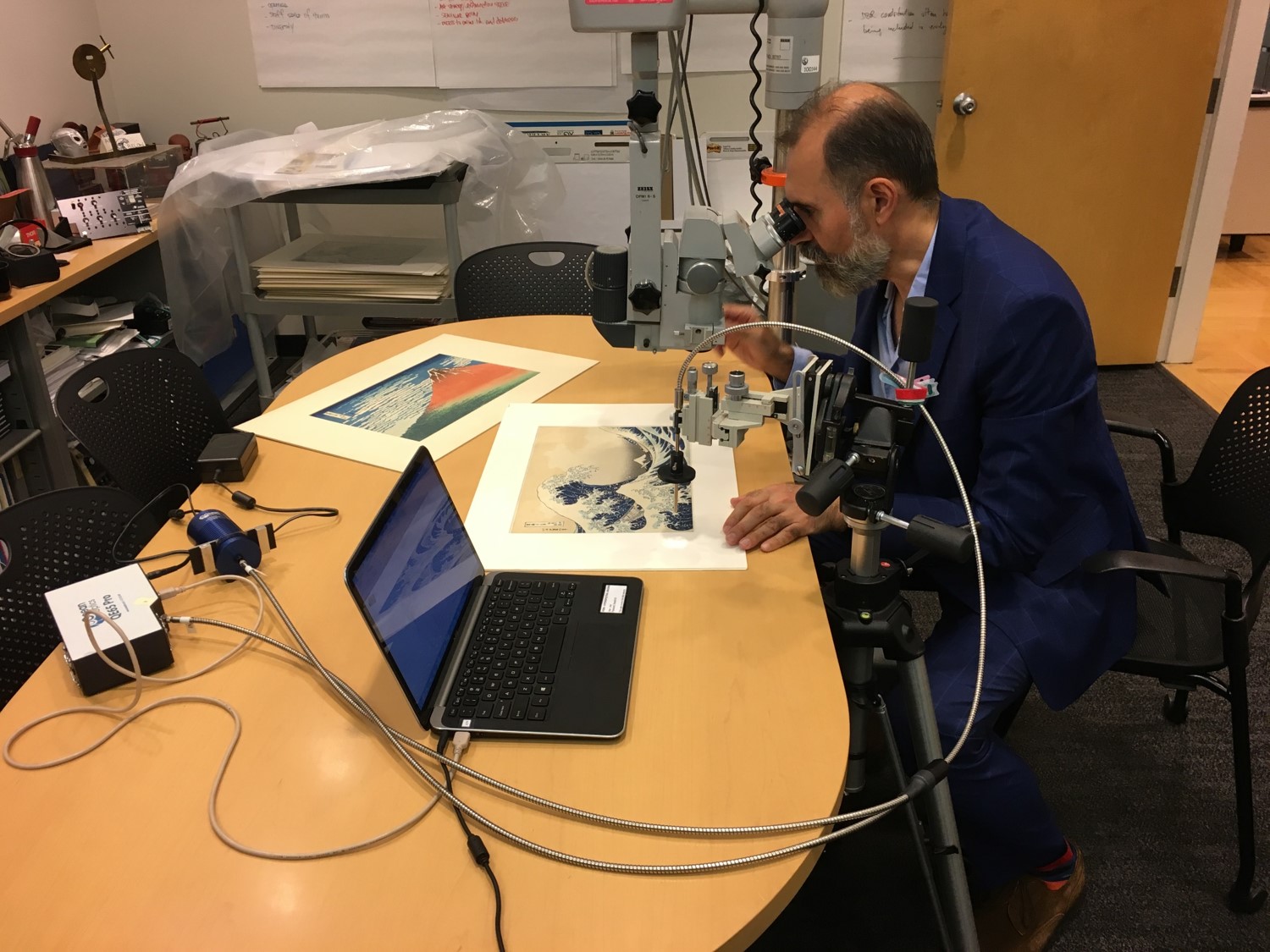

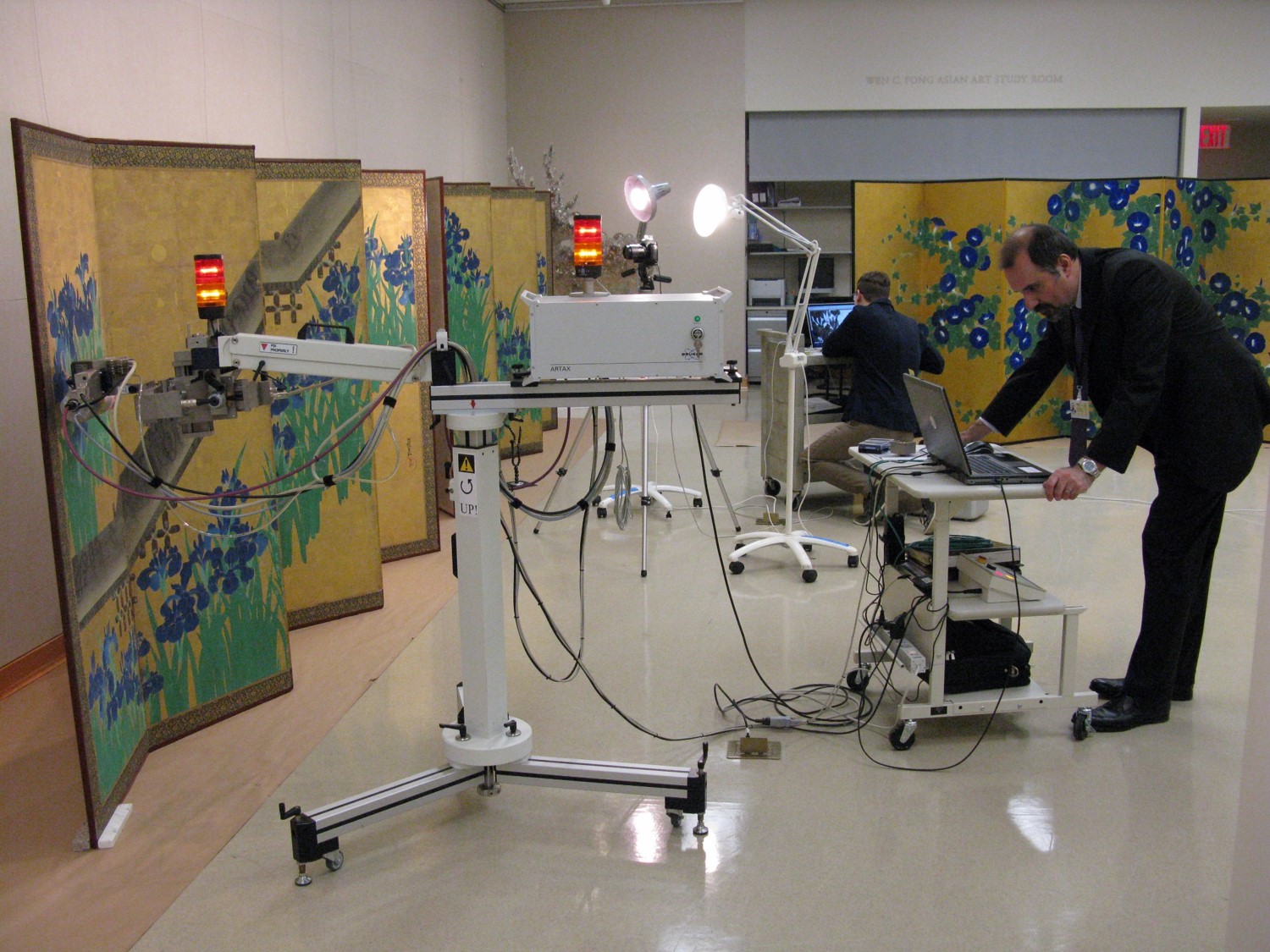

I also work on Japanese art. That’s my skill, my passion. I’ve done a lot of work to study artworks such as the famous Great Wave by Hokusai. If you Google me you’ll see that I talk a lot about that. Our job is to discover how those prints were made, and also to really look through materials, through the technology, through the identification of artists pigments and processes, and understand more about the society that produced these works.

Our aim would be not to just stop at the surface or under the surface, but scrape down and tell a story that really says something new about Hokusai and understand art through the lens of the components and physical nature of the object.

How do you apply your scientific expertise to the artworks that the museum deals with? Can you give an example?

For example, in Hokusai’s Great Wave (you can look up in our collection website) you see there’s a beautiful and dynamic live representational force of nature in the Great Wave where tiny little men are about to be washed out by the wave. One of the things that was very interesting to me was the use of blue. Now the woodblock printing in Japan in the 1800s was the most advanced color reproduction technique in the world. So even though it was a pre-industrial society, there was no steam power, no machine, etc., they could achieve amazing results in several fields.

They were able to achieve amazing color quality, amazing quality control over print that were sold at a very low cost. It was commercial illustration, it was not art. You start seeing prints like the Great Wave, my own hypothesis is that we have the beginning of artistic prints in that they go beyond even what was already highly achievable at that time in the sense that the depth of color and the color range is amazing. Our brain processes variations in light (expressed in drawings with light and dark shading) as variation in depth in space. Hokusai and the master craftsmen who printed this work knew this intuitively, and they took extra care with lighter and darker shades of blue to create depth and movement. The observation is that these works are truly exceptional, and trying to deconstruct them to see what makes them amazing in the use of color and then going into analysis to prove this theory is part of the work. Therefore, we use a variety of tools, and the most important ones are the eye and the microscope, as you really want to get close to it and observe it. I’m not that good but my colleagues that work in conservation really have highly trained eyes and they can very often tell me what I’m going to find. They are always right. And then we go on with non-invasive analytical techniques. These are instruments that allow us to identify the materials without removing particles from the work, eventually it may be necessary to do what we call micro sampling, that is removing microscopic fragments.

We have a fiber optic instrument that shines just like regular white light and we capture the reflection of the color, and we can see through a spectrometer broken down in each wavelength rather than the eye which has only three receptors, the eye sees blue, green, and red.

Blue, green, and red are amazing colors because we have color vision essentially by seeing these three colors. This instrument instead has hundreds of receptors so we can really get a very complex picture that gives us the fingerprint of a certain color. We can tell whether it’s Indigo or Prussian Blue.

So what we discovered was how those two pigments were mixed which makes the printing more complex, time consuming, and ultimately more expensive, if you see that the publisher chose to go through this route and created something that clearly has more added value, more artistic quality. Then, this is not a normal print, and I think that that is an important statement to make because it says something about the time that was done and what people wanted and it gets a bit more complex. You can imagine that landscapes are important to those who love to travel. And that’s normal for us. We don’t even think about it. You have a landscape in front of you and say, oh I would like to visit the place or I visited that place. I think about older times like special feudal society when they were not allowed to travel and could not just pick up and go with money; but also needing to be authorized by their local sovereign lord. You could not just go somewhere else and not work for him.

So what we see in Japan in Tokyo is that people had a little bit more money and

people started traveling. So maybe it’s a pilgrimage. Maybe it’s going to a famous sanctuary or famous art place. So if you’re a person of means you travel and you commission a painting that shows a famous place.

If your personal means are less you may buy a print and maybe still travel so the print could be a souvenir. If you’re somebody who cannot travel at least you can afford the print because now you see the landscapes around you. There is always a correlation of what you see in paintings and what you need to make that painting.

Before the 1820’s (The Great Wave is from 1830s) you cannot find landscape prints in Japan.

Quite simply because they didn’t have a blue color that you can use for print that would give you the bright blue of the sky and the deep blue of the ocean. All they had was indigo, which is the color of blue jeans, a bit of a dull color. It doesn’t really work. If you make it really concentrated it comes out a dull grey-blue.

If you want to you can make it a little like the blue sky but it won’t be the real blue sky and so at some point Prussian blue from Europe arrived in Japan. And that’s about 1820 the moment it arrives you have landscape prints. This is not a coincidence.

We traced the use of colors which is the very basic step into looking at a piece of art with the curators or art historians. We then join in and so it’s a little bit of a forensic conversation, a little bit of art historical background. We go in through a step-by-step approach using not the eyes but microscopes, for non-invasive analysis as well as x-ray laser based infrared tools.

Have you ever come across a forgery?

We generally don’t comment on forgeries and similar issues. There are other issues which are not outright forgeries, but it’s where a piece has been restored and and so a part is not original and some of them could be historical and some could be very new. So it’s more about deciding which one stays and which one goes. I know it’s a very fascinating topic, but I am sure there are actually less forgeries than you think. We haven’t seen many those. We also have the opposite which is when we have an object that may be classified as a reproduction or a copy and with true analysis we can tell that it’s actually the real thing. That’s far more exciting because instead of condemning something you can actually bring it back from obscurity.

What do you think of the art world right now during Covid-19? What has the impact been as far as you see?

I can tell you only what I know about-that it is certainly a crisis.

This is hitting all of us really hard.

I say it’s a catastrophe because right now the MET is losing an enormous amount of money. We’re trying to stay open and we really wanted to stay open, not so much to find revenue. As you know, we have a particular admission policy where New Yorkers and New York State residents “pay as they wish”.

The fixed price ticket is only for people outside of the State of New York. But with Covid the only people who come to the museum are New Yorkers and New York State residents. Our revenue is very small right now and really I would say the decision was to open because we think we represent something for the city for our members, for our public, and we wanted to be there.

The reopening was not about the money. As you look at museums closing around the country it’s very sad and I hope that museums can stay open and will decide to stay open if they can.

It is a great time now to visit and experience the museum because there are only very small crowds. Everybody is wearing a mask. Everybody is distancing. You can relax in the galleries.

What has been the most challenging part of your job?

We are a frontier profession but the field is still making advances that are considerable. Also we are at the border between different disciplines so it’s really a matter of communication. It’s really learning the language of other professions while communicating our work in a way that is responsible and relevant to others, and fighting every day for our own relevance. Really the ones at the table are the ones being part of the messaging in every sense.

What has been the most enjoyable part of your job?

I like to talk all over the world about my profession. I’ve been honored to be with scientists who achieve far more than me and we talked to school children and we see them get excited when we bring them here in the labs. We want to do more and more of that. That is absolutely enjoyable.

Then, the other part that is amazingly enjoyable is being in the lab and developing something new, creating a new instrument, making a new discovery. That is something that by itself is worth all the work that you put in.

Then, the other part that is amazingly enjoyable is being in the lab and developing something new, creating a new instrument, making a new discovery. That is something that by itself is worth all the work that you put in.

You most likely do not work alone. What kinds of things do the team members do to assist you with your work?

The staff is highly specialized: chemists or geologists. Most of them are with PhDs where 80% are women, 20% men. Every year we have two to three postdoctoral fellows. We have had over 200 since I came here: interns from High School to graduate, undergraduate to graduate, and post graduate fellows to high level scientists coming.

That’s a very broad crew. We have people specializing in different areas. So I have a person who specializes in analysis of paintings, a person specializing in organic material now. This is sort of the oil, the tempera order. We have a person specializing in organic analysis for the rest of the collection. We established it recently, three people who are in charge of the environment. They study air quality, temperature, humidity, and light conditions.

It’s a luxury to have so many. We’re probably the largest in the US in a museum.

These types of diversity of scientific training and discipline is very important when you think of an art museum like the MET. We collect anything and everything from ancient Asia art

to the contemporary world. There isn’t another museum in the world that has a collection so broad and I don’t mean this to brag. For example, the British museum has the widest archaeological collection but does not have the diversity of art that the Met museum has.

It doesn’t matter how big you are, but it’s about the diversity.

Leave a comment