New York, NY – Monday, May 6, 2013

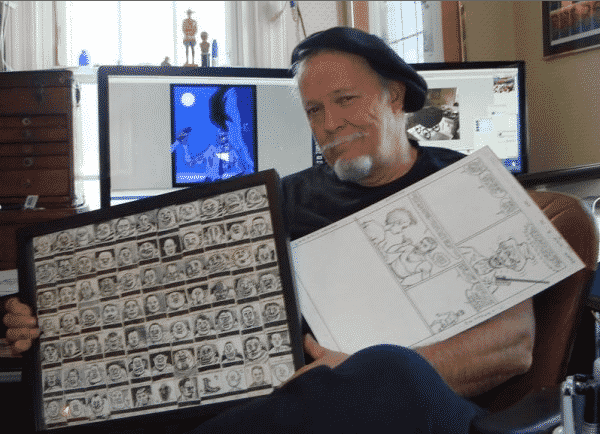

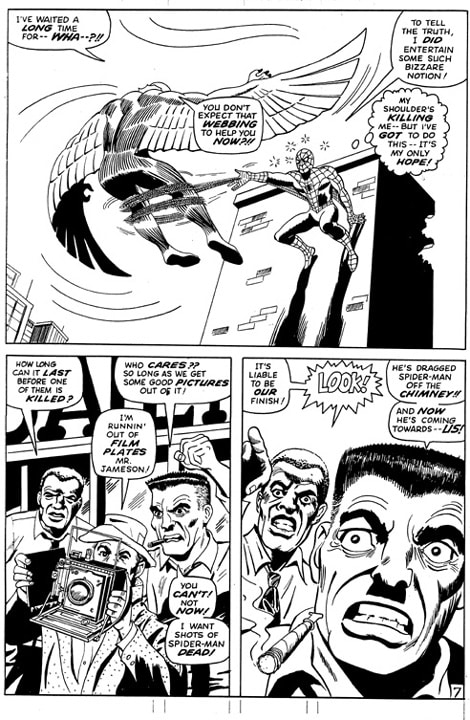

If you don’t recognize the legendary humor cartoonist Rick Parker by name or by his face, you’ve seen his work. If you were a fan of Marvel comics in the 90s you’ve seen it whether you realize it or not. His 1-3 panel Bullpen Bulletin strips were printed on the fan page in every Marvel Comic book during the comic book boom. In modern technological jargon, that’s billions of impressions. He’s penciled, inked, or lettered over 30,000 comic book pages, and although Rick is extremely humble about it, he’s literally one of the most published cartoonists in modern history.

Rick and his family recently moved from a NYC suburb to Fallmouth, Maine, an artsy town just a mile or two above Portland where he’s now somewhat of a local art celebrity. As Rick put it “It is a very cool place full of artists and cartoonists… a city with character and balls.”

Although he’s far away from NYC, Rick maintains his very active social media presence, posting several times daily to Facebook. Always humorous, entertaining, informative or funny his posts are usually image heavy: New drawings, photos from art shows, pictures of book signings, or retro photos of himself in his NYC Fine Art days of the 70s and 80s.

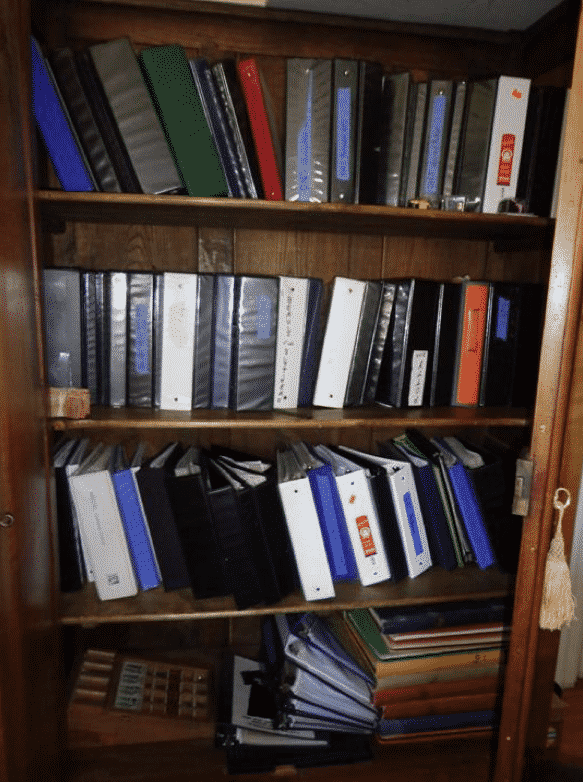

A set of wooden shelves stacked to the brim with binders full of drawings.

Then a few weeks ago, from out of the blue he posted this picture with a shocking status description:

FOR SALE: My Life’s Work. Thousands of pages of drawings, ideas, sketches, writing, photographs, comics strips, comic art, scripts, sculpture, collage, lithographs, mementos, etc. going back forty years many published, many unpublished. All in binders and various suitcases and portfolios. Includes basically everything I have done worth keeping in my adult life plus a great deal more of original comics pages, sculpture and paintings. $1,000,000 to a good home. Please share. Thanks.

– Rick Parker

I asked him if this was serious. He told me he was. He is looking to retire his life’s worth of work to the right art collector or institution.

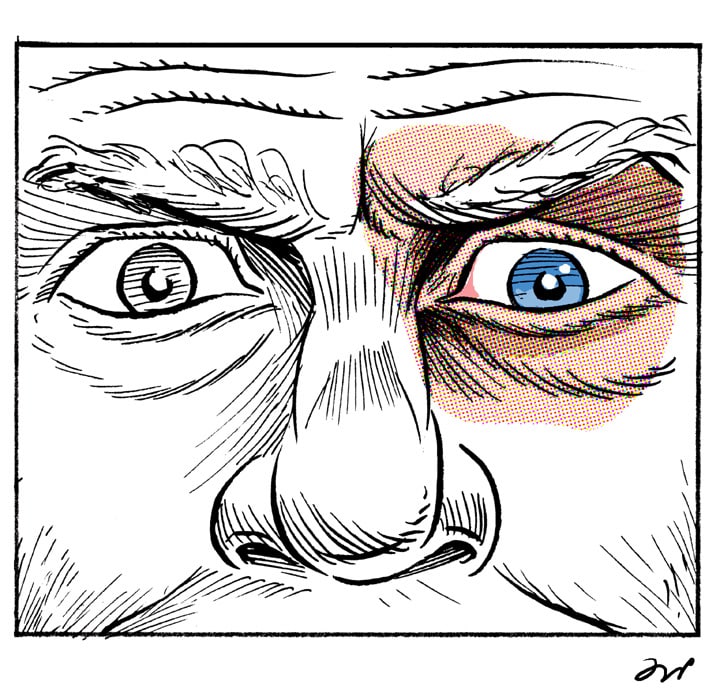

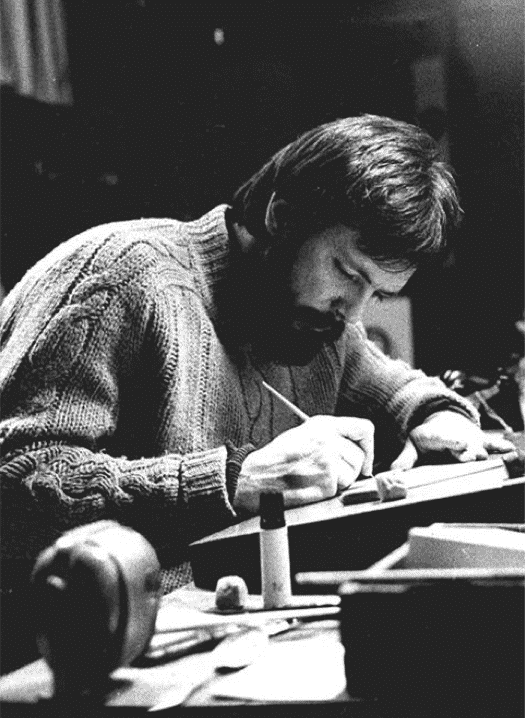

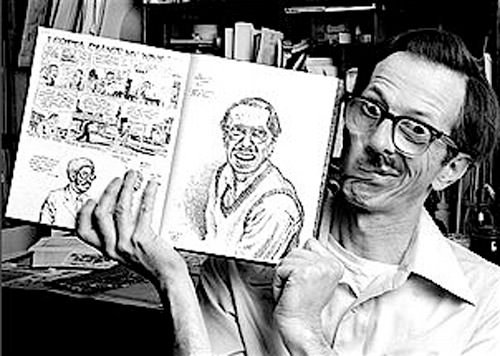

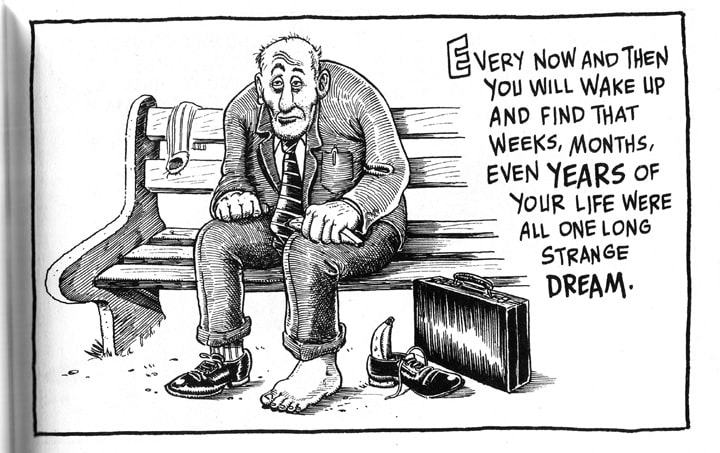

I instantly thought of cartoonist R.Crumb (pictured above) when, as documented as part of the 1994 art biopic CRUMB, he traded six sketch books for a house in the South of France where him and his wife still live to this day (talk about the original one red paperclip).

From the looks of the bookshelves full of work (which is just the tip of the iceberg), Rick seemed to be putting a lot more on the table than six sketch books. His entire career’s worth of work in one fell swoop.

But I knew if I were to write a story about this and let the world know that this offer was on the table, it would be smart to be able to categorically break down in pictures and words “What exactly is in all of those binders?”

Portraits by Micha Hamilton.

It’s not easy to set the table for the possible sale of a drawing collection this massive and broad in scope. Being an amazing writer, among his other talents, Rick got back to me with what you are about to read after only a few hours of requesting it from him. He decided to fully explain his long and storied career in the NY art scene and Marvel comic books in a story (punctuated by images). His life story in art, section by section, work by work.

I was not only honored that he put the time into this for us, but also astonished that he had never actually written this stuff down before. It’s basically an outline for one of the great artist autobiographies that has yet to be written. I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I did, and if you are a serious collector, this could be an opportunity of a lifetime.

DRAWING A CROWD by Rick Parker

DRAWING A CROWD by Rick Parker

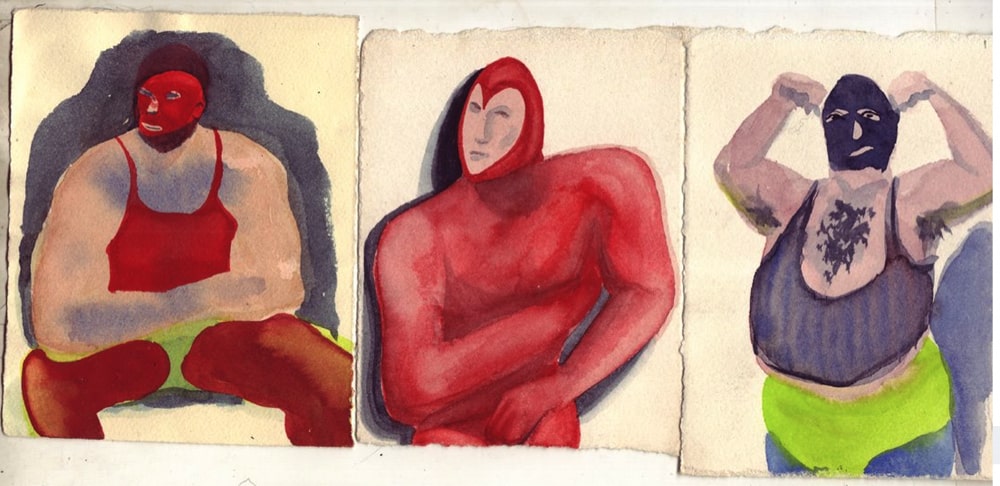

The “million dollar offer” basically includes most all of the work I have done since moving to New York City to attend graduate school at Pratt in 1973. To me, my arrival in New York to “find myself as an artist” and pursue my “fame and fortune” as an artist really started then. I knew no one in New York so when I wasn’t attending classes, I was “holed up” in an empty basement apartment in Bedford Stuyvesant doing watercolor paintings of wrestlers which I improvised from my head. There are about 50 of those. At the same time, I did collages on blank postcards I obtained from the post office on the corner for 5 cents each and pasted words and pictures on them which I cut out of newspapers and magazines.

I mailed these postcards to friends and family down South. I began receiving postcards of a similar nature from my former painting professor at the University of Georgia and subsequently began directing two or three cards to him each day. All in all I probably sent him over 700 cards. He mounted a show of many of them at The University in 1974 called “Correspondence”. I did not attend the opening as I was living in NY at the time and had very limited resources.

I mailed these postcards to friends and family down South. I began receiving postcards of a similar nature from my former painting professor at the University of Georgia and subsequently began directing two or three cards to him each day. All in all I probably sent him over 700 cards. He mounted a show of many of them at The University in 1974 called “Correspondence”. I did not attend the opening as I was living in NY at the time and had very limited resources.

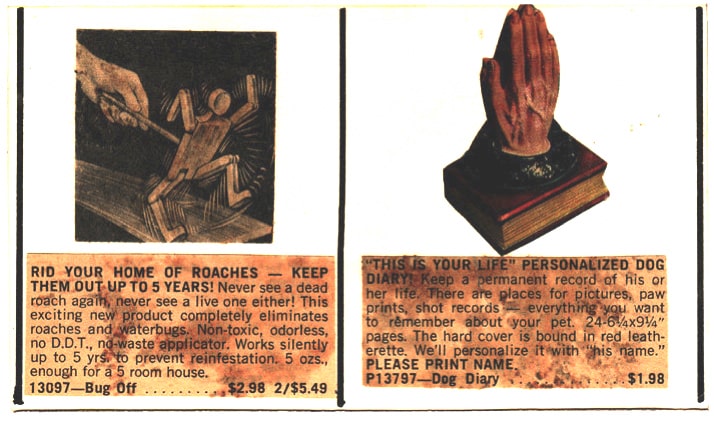

The next phase of my development was multi-pronged and explorational. While still a student, I produced a series of lithographs using the traditional approach to lithography by drawing on Barvarian Limestone and printing editions of twenty or twenty-five images based on words and images from the New York Newspapers.

The next phase of my development was multi-pronged and explorational. While still a student, I produced a series of lithographs using the traditional approach to lithography by drawing on Barvarian Limestone and printing editions of twenty or twenty-five images based on words and images from the New York Newspapers.

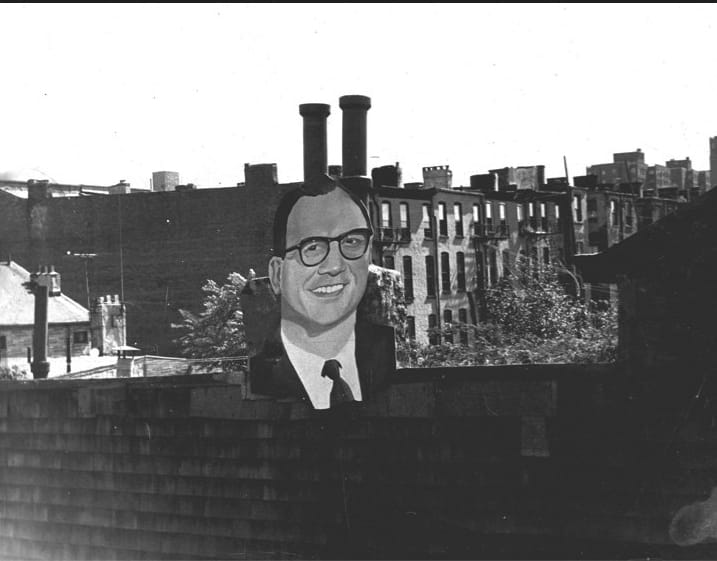

I also did large realistic paintings of people, the most interesting one of which is of the smiling face of a man, which I attached to the outside of my building which was next to the Brooklyn Queens Expressway near the Navy Yard. Traffic often came to a standstill and I could see the faces of bored motorists from my bedroom about 100 feet from the roadway.

I also did large realistic paintings of people, the most interesting one of which is of the smiling face of a man, which I attached to the outside of my building which was next to the Brooklyn Queens Expressway near the Navy Yard. Traffic often came to a standstill and I could see the faces of bored motorists from my bedroom about 100 feet from the roadway.

I thought I would mount an impromptu exhibition just for them. At the same time I was also walking the streets of Brooklyn and picking up flattened out cans and prying lost heel plates from the streets which had become embedded in the tar.

These things I nailed or tacked to 3/4″ plywood rectangles until the surface was completely covered in a tin collage. I do not have any photos of these. The next phase of my work consisted of a series of hundreds of different “window Installations” at my studio at 46 Grand Street. We called it the Barking Dog Museum.

These installations consisted of found objects combined with words and were visible to passersby on the street. I kept this up for 12 years–even after I had begun working at Marvel full time. A prominent New York Art Dealer came to the show and told my ex-wife I had a “great mind”. I believed her.

These installations consisted of found objects combined with words and were visible to passersby on the street. I kept this up for 12 years–even after I had begun working at Marvel full time. A prominent New York Art Dealer came to the show and told my ex-wife I had a “great mind”. I believed her.

Working at Marvel was just a way for me to make some money and I still thought of myself as a fine artist, although I could draw very well since was a young boy. I had done a couple of covers for SCREW in New York, because I saw that Wally Wood was doing that so I thought it must be a good thing. Wood was one of the artists whose work I had seen as a child and I thought he was the greatest. I showed these as samples when I tried to get art at Marvel in ’74. Dan Adkins was not impressed and looked at me like I was crazy.

Working at Marvel was just a way for me to make some money and I still thought of myself as a fine artist, although I could draw very well since was a young boy. I had done a couple of covers for SCREW in New York, because I saw that Wally Wood was doing that so I thought it must be a good thing. Wood was one of the artists whose work I had seen as a child and I thought he was the greatest. I showed these as samples when I tried to get art at Marvel in ’74. Dan Adkins was not impressed and looked at me like I was crazy.

Later I saw an ad in the NYT for a letterer and because I had once dated a girl who did that for Marvel I applied for the job. It turned out to be for Marvel and they hired me and I set about working very hard for them doing lettering, although I felt like I was not living up to my potential. My fine art gradually tapered off as I spent more and more time lettering comics for money.

It is interesting now, especially at my age, to think about the overall trajectory of my “art career”. I now see relationships between what came before and what resulted–how one thing led to another….which I find interesting.

It is interesting now, especially at my age, to think about the overall trajectory of my “art career”. I now see relationships between what came before and what resulted–how one thing led to another….which I find interesting.

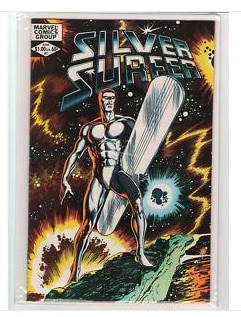

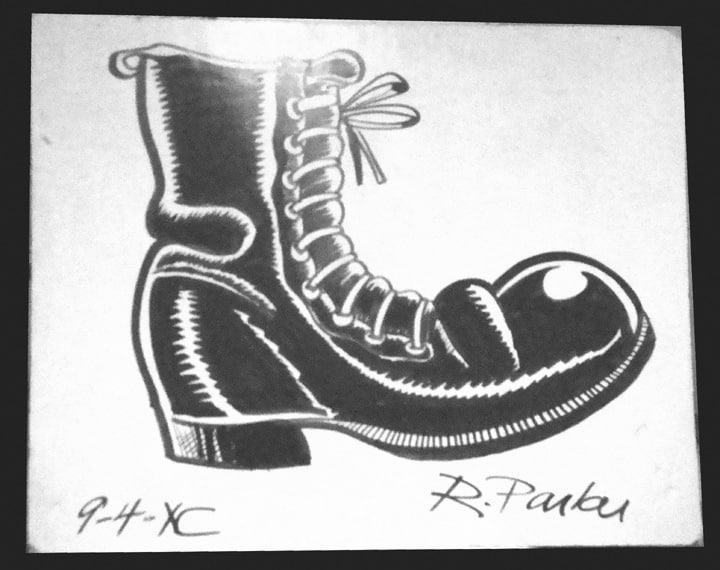

I dabbled in logo design briefly, but never enjoyed the “competitive” aspect of it. I was never comfortable when they picked my design over others and was even more uncomfortable when they didn’t. However, since I was asked to letter the interior of the Silver Surfer book by Stan Lee and John Byrne, they let me design the logo. Thirty-three years later they’re still using a modification of my design (which I don’t like) and I designed my own version of the character.

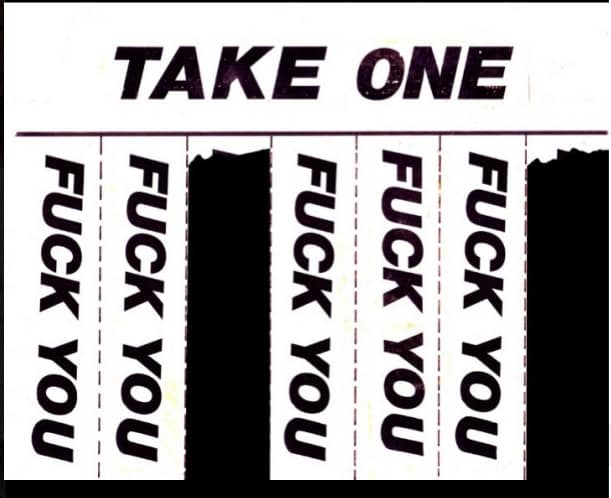

The most active period of the Barking Dog Museum was from 1976 until around 1982 by which time I was staying at the office (after working an 8 hour day) doing freelance lettering and paste-ups until the cleaning lady turned out the lights about 11:30. During this period I suppose you could say I found an outlet for my “creative” side by “re-writing” the dialogue in existing comics stories and using the office’s photocopier to produce “notices” which I would place on the office doors or bulletin boards around the company.

The most active period of the Barking Dog Museum was from 1976 until around 1982 by which time I was staying at the office (after working an 8 hour day) doing freelance lettering and paste-ups until the cleaning lady turned out the lights about 11:30. During this period I suppose you could say I found an outlet for my “creative” side by “re-writing” the dialogue in existing comics stories and using the office’s photocopier to produce “notices” which I would place on the office doors or bulletin boards around the company.

One example would be TAKE ONE and then six or seven pieces of paper with the words FUCK YOU easily torn off using the dotted lines. Another might be just the words, “WEDNESDAY, MARCH 13, 1983” in big bold letters on a piece of paper. These were done using “Press Type”. I would also do drawings of faces and then move the paper around on the press bed of the photocopier to distort it randomly.

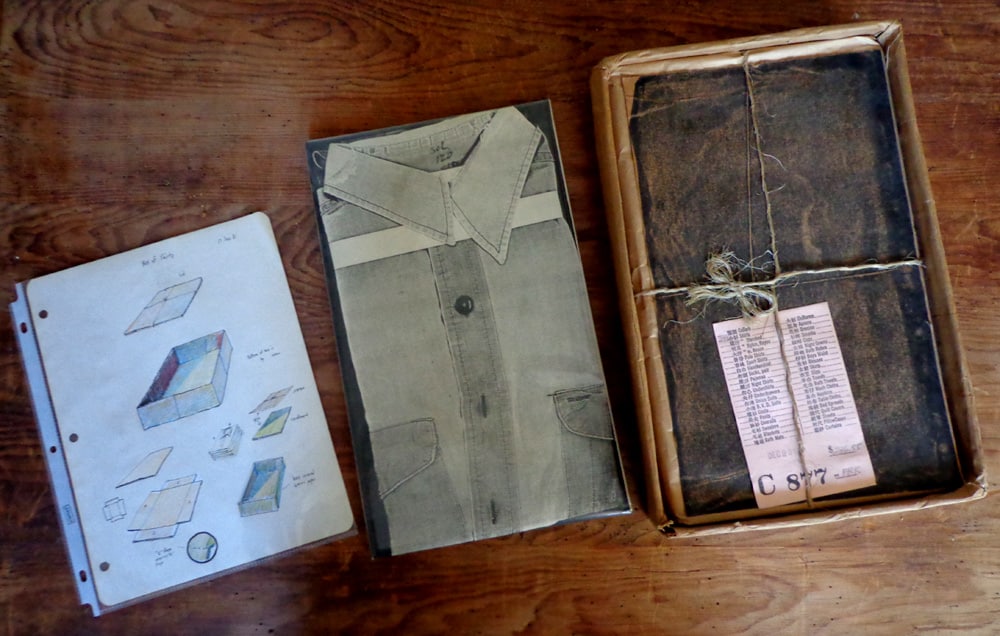

Perhaps the best photocopy art that came out of this form of exploration was a cardboard box containing 100 photocopies of a starched and pressed ragged old shirt. These “prints” were then wrapped up in brown paper and tied with a string and a Chinese Laundry ticket attached to it. Then this was photocopied on brown wrapping paper and this was wrapped around the whole. It was like an Egyptian mummy in a way.

Perhaps the best photocopy art that came out of this form of exploration was a cardboard box containing 100 photocopies of a starched and pressed ragged old shirt. These “prints” were then wrapped up in brown paper and tied with a string and a Chinese Laundry ticket attached to it. Then this was photocopied on brown wrapping paper and this was wrapped around the whole. It was like an Egyptian mummy in a way.

In 1977 I applied for and was the recipient of a grant from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs (a CAPS grant) which was intended to subsidize my exhibitions at the Barking Dog Museum. By this time I was making good money at Marvel and had a staff job. I spent the grant money on a motorcycle, which I drove into my ground floor apartment in NYC each evening.

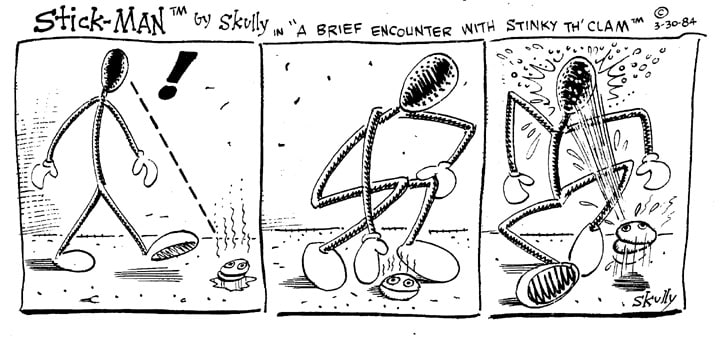

In 1981, I did about a dozen cartoon strips based on a very eccentric friend I had met in Brooklyn. It was called “George” and I was surprised when an editor at Marvel expressed an interest in it. That editor was Jim Salicrup, who later proved to be a very important person in my development and gave me many of my first “breaks” as an artist as well as keeping me supplied with much-needed freelance work. Around 1983 I decided to do a cartoon strip featuring a stick figure (“Stick-Man”) and several of his wacky associates (Stinky The Clam, Professor McNutt, Mr. Happy and Fat Man). These I posted on various office doors and bulletin boards at night. My fellow employees would come in the next morning and seemed amused by them. I produced 100 copies of a spiral bound “Stick Man Calendar for 1984” and gave everyone in the office a copy and mailed out many others to people like Art Spiegelman and Russ Cochran.

About this time, the Editor in Chief told my boss he was uncomfortable with the fact that I was doing freelance lettering in the office, even though I had finished all of my current work for which they had hired me and had been told when I was hired that when I finished the work for which I had been hired, and things were slow, I could make a little extra money doing freelance lettering” rather than just sit there.

About this time, the Editor in Chief told my boss he was uncomfortable with the fact that I was doing freelance lettering in the office, even though I had finished all of my current work for which they had hired me and had been told when I was hired that when I finished the work for which I had been hired, and things were slow, I could make a little extra money doing freelance lettering” rather than just sit there.

If they weren’t going to let me work on freelance work at the office I couldn’t make very much money from my staff job, so I quit my full time job to be a freelancer. My boss graciously allowed me to continue to sit in the office and work on my freelance work for the company even though I was no longer a part of the staff. Finally they told me they needed my desk space and that I could work from home. They gave me a contract and told me they would send messengers back and forth for my output.

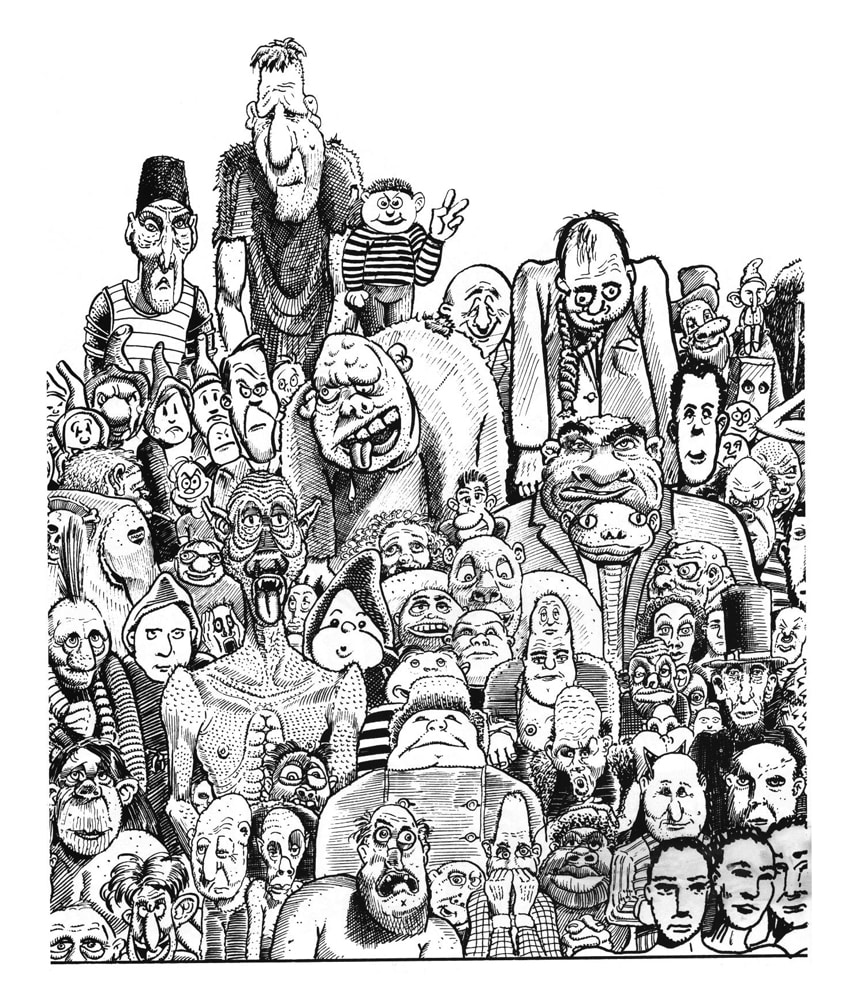

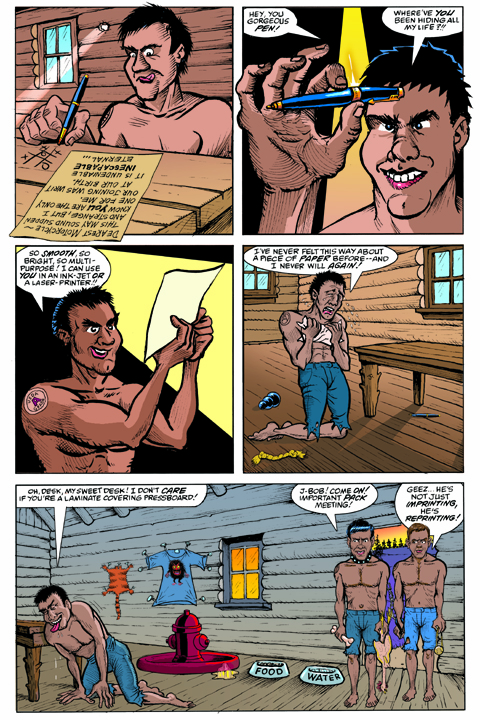

This turned me into quite a productive worker as all I had to do was stay home and work 12 to 14 hours a day. It also helped usher in a new phase of my work as it was during this time that the focus of my creativity switched from assembling objects in space to drawing pictures. I kept a big piece of paper next to my drawing board to test my pen on before setting it to work on the pages for Marvel. But instead of just making random marks they way one would normally test a pen, I would draw or doodle cartoon figures just standing there. Before long a crowd of hundreds of strange figures had started to appear. I was literally “drawing a crowd”.

This turned me into quite a productive worker as all I had to do was stay home and work 12 to 14 hours a day. It also helped usher in a new phase of my work as it was during this time that the focus of my creativity switched from assembling objects in space to drawing pictures. I kept a big piece of paper next to my drawing board to test my pen on before setting it to work on the pages for Marvel. But instead of just making random marks they way one would normally test a pen, I would draw or doodle cartoon figures just standing there. Before long a crowd of hundreds of strange figures had started to appear. I was literally “drawing a crowd”.

When I covered most of the paper I looked at it and had an epiphany. It was a moment in time when I thought perhaps I should concentrate more on cartooning and less on fine art. There seemed to be a lot locked up inside me which needed to come out. I began doodling on the outside of the envelopes with the comics pages in them while waiting for he messengers to arrive. This was the beginning of another important phase in my development.

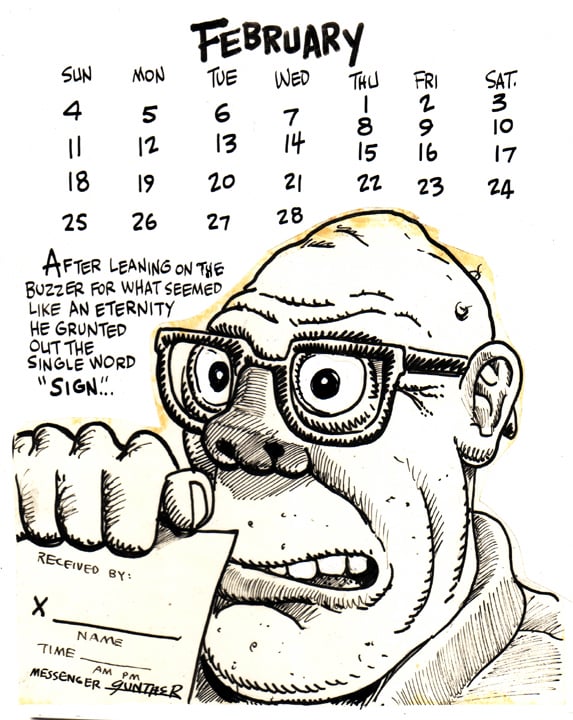

One day, many months later, when I was visiting the office, I was surprised to see that many of these casual doodles on the envelopes had been carefully cut out and preserved by some in the editorial department and I took this as all the encouragement I needed to continue doing it. Jim Salicrup, an editor at Marvel liked what I was doing and proposed I do a “Messenger Calendar” for 1990 and gave me a thousand dollars to have 1,000 copies printed up. We signed them and wrote the recipient’s name on each one to make it look like it had been printed on the calendar. We distributed these to everyone we knew or could think of who might be interested and sold some others at comic book shows.

One day, many months later, when I was visiting the office, I was surprised to see that many of these casual doodles on the envelopes had been carefully cut out and preserved by some in the editorial department and I took this as all the encouragement I needed to continue doing it. Jim Salicrup, an editor at Marvel liked what I was doing and proposed I do a “Messenger Calendar” for 1990 and gave me a thousand dollars to have 1,000 copies printed up. We signed them and wrote the recipient’s name on each one to make it look like it had been printed on the calendar. We distributed these to everyone we knew or could think of who might be interested and sold some others at comic book shows.

Editors and others were starting to take note and offered me a few random assignments doing drawings or reprinting some of my work in the backs of their comics or doing an occasional cover or five page “back-up” story.

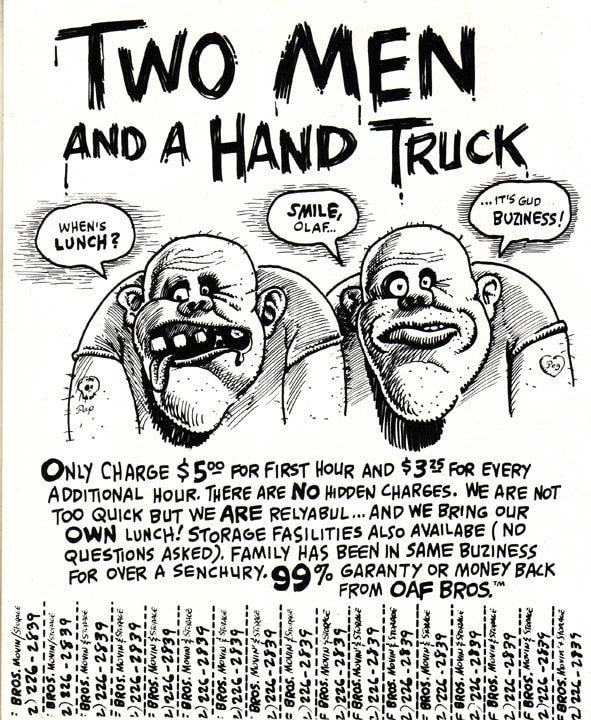

Inspired by Jim Salicrup’s dashed off parody of TOP GUN, a popular film at that time, I decided to produce a cartoon strip of his character TOP BUM. It was politically incorrect and featured a WC Fields-like man in a tattered tuxedo begging money along NYC’s Park Avenue and conning people and kids out of money which he then spent on expensive champagne to stay inebriated. Another strip I did about this time and showed to people was about two intellectually challenged twins who worked in the “moving business” transporting people’s property from one place to another. This was called “OAF Bros.”

Inspired by Jim Salicrup’s dashed off parody of TOP GUN, a popular film at that time, I decided to produce a cartoon strip of his character TOP BUM. It was politically incorrect and featured a WC Fields-like man in a tattered tuxedo begging money along NYC’s Park Avenue and conning people and kids out of money which he then spent on expensive champagne to stay inebriated. Another strip I did about this time and showed to people was about two intellectually challenged twins who worked in the “moving business” transporting people’s property from one place to another. This was called “OAF Bros.”

Around this time I began drawing on blank matchbook covers which I had picked up from cigarette machines in bars that I frequented at night when my ex-wife and I would meet about 10:30 each night.

Around this time I began drawing on blank matchbook covers which I had picked up from cigarette machines in bars that I frequented at night when my ex-wife and I would meet about 10:30 each night.

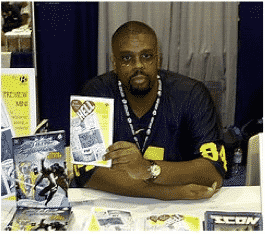

Photo Credit: Bangor Daily News.

Photo Credit: Bangor Daily News.

I would draw a face on one side and write a mini-biography on the other. These were just imaginary people and many of them closely resembled inmates of penal institutions or escapes from mental wards. On nice days I would take a break from my work and sit at a TV tray in front of my apartment or in front of art galleries in my neighborhood doing these drawings and placing them on the TV tray . To my amazement people were buying them for “three dollars each, two for five and no reasonable offer is ever refused”.

I met many famous and notable people this way and began taking longer and more frequent breaks from my lettering work in comics. I began doing comics shows in NYC. By now several editors were interested in working with me but my personal life had deteriorated to the point where I was going through a messy divorce and finding a new place to live. The timing could have been better. A friend who ran an art gallery in New York offered me a show in 1990. I did twelve large drawings on foam core and called the show, “TWELVE UGLY DRAWINGS” mainly because my mother said my work was “ugly”.

I met many famous and notable people this way and began taking longer and more frequent breaks from my lettering work in comics. I began doing comics shows in NYC. By now several editors were interested in working with me but my personal life had deteriorated to the point where I was going through a messy divorce and finding a new place to live. The timing could have been better. A friend who ran an art gallery in New York offered me a show in 1990. I did twelve large drawings on foam core and called the show, “TWELVE UGLY DRAWINGS” mainly because my mother said my work was “ugly”.

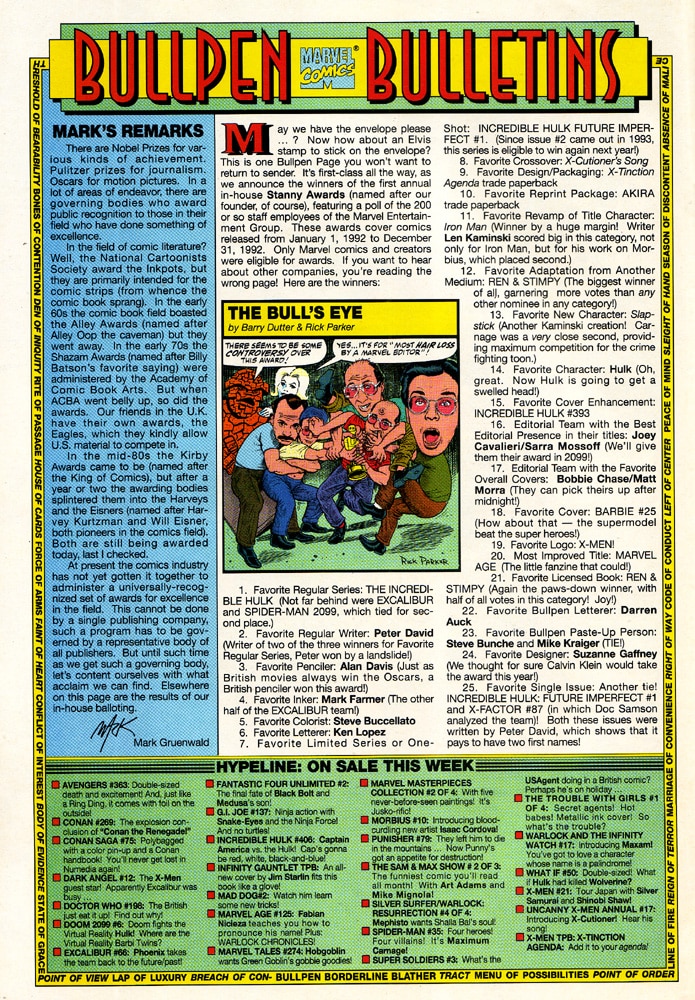

Several young ambitious writers and editors wanted to work with me and I did a couple of stories which appeared here and there tucked away in various Marvel publications. One young fellow, Barry Dutter, had an idea for a humor book and asked me to do some sample illustrations for it. He very quickly succeeded in getting several publishers interested.

That book was “Everything I Really Need To Know, I Learned From Television” (Applause Theatre Books,1992). Along about that time, I met my wife, the love of my life and became a much happier person than I had ever been before.

A few things happened around this time which helped me establish myself in the eyes of my co-workers and comics fans. Executive Editor at Marvel, the late Mark Gruenwald approved of a single panel gag cartoon to appear on the editorial page of almost every title Marvel was publishing at the time. It was called “The Bullpen Bulletin” and featured Marvel characters in funny imaginary situations dreamed up by my former collaborator, Barry Dutter, and illustrated by me. Mark informed me that this made me the “most published” cartoonist in the history of the world as our cartoon was printed in approximately six million comic books each week!

A few things happened around this time which helped me establish myself in the eyes of my co-workers and comics fans. Executive Editor at Marvel, the late Mark Gruenwald approved of a single panel gag cartoon to appear on the editorial page of almost every title Marvel was publishing at the time. It was called “The Bullpen Bulletin” and featured Marvel characters in funny imaginary situations dreamed up by my former collaborator, Barry Dutter, and illustrated by me. Mark informed me that this made me the “most published” cartoonist in the history of the world as our cartoon was printed in approximately six million comic books each week!

The printed panel was in color and 2.75 inches square. I figured out that if someone was to cut out each panel and tape them all together in a long line it would stretch to the moon and possible beyond. I didn’t really have an affinity for superheroes and finally asked if I could be the one to come up with the ideas for the cartoon. Barry said it was okay with him, as he was being paid the same money for writing the whole page and it was less work if he didn’t have to come up with the ideas.

Mark agreed to let me do it and the focus shifted from the superheroes and villains to the fans themselves and various people who worked in comics. This gave rise to a black and white cartoon strip which appeared in Marvel Age called “The Bossmen”. It basically made fun of my boss and the people I worked with. It was edited by Steve Saffel and my co-workers seemed to mildly amused seeing themselves portrayed in humorous situations, although the main focus was on Tom DeFalco, the editor in chief at the time.

Mark agreed to let me do it and the focus shifted from the superheroes and villains to the fans themselves and various people who worked in comics. This gave rise to a black and white cartoon strip which appeared in Marvel Age called “The Bossmen”. It basically made fun of my boss and the people I worked with. It was edited by Steve Saffel and my co-workers seemed to mildly amused seeing themselves portrayed in humorous situations, although the main focus was on Tom DeFalco, the editor in chief at the time.

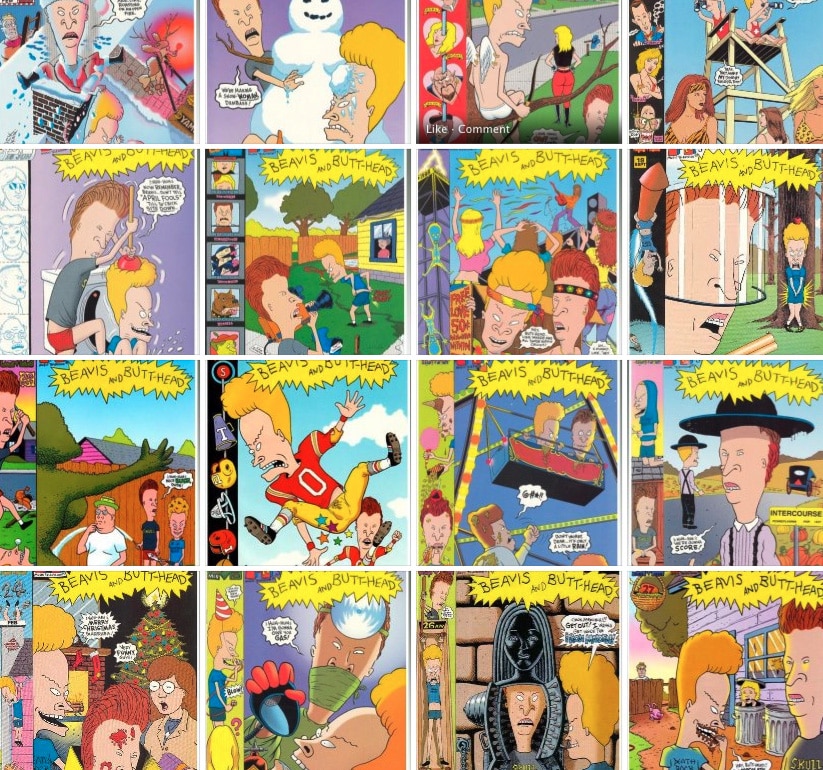

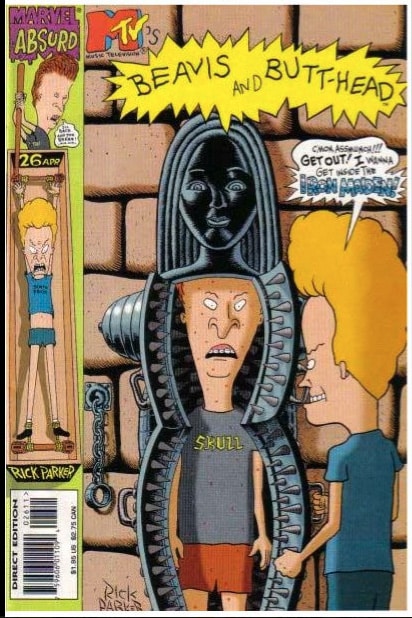

One of the young editors who had been an assistant in Jim Salicrup’s office and gotten a kick out of my drawings on the outside of envelopes, got promoted to editor. His name is Glenn Herdling and he once told me he liked what I was doing and if he ever got a chance, he would hire me to work with him on some project. Glenn was known as a funny guy and so when Beavis and Butt-Head came to Marvel, naturally, he was put in charge of it. He kept his promise and hired me to do the art. At the time it was the hottest entertainment property in the country and the timing could not have been better.

I started working on the first issue in October of 1993, right as our first child was being born and the first issue came out in January of 1994. It was the second best selling comic of the year and sold 600,000 copies. It sold for $1.75 and as the penciler and inker I made five cents on each issue sold once it surpassed 100,000 copies—or half a million nickels. That’s a lot of nickels. Fortunately, they paid me by check. I quit all other work, hired two assistants and I worked on that book exclusively for the next two and one half years.

During that time, I was asked by Joe Orlando to try out for Mad Magazine and didn’t give it the attention I should have. A decision I would soon regret and will regret for the rest of my life. The first 20 issues of Beavis and Butt-Head Comic Book were in the top 100 books sold each month. In those days there were about 10,000 things to choose from.

During that time, I was asked by Joe Orlando to try out for Mad Magazine and didn’t give it the attention I should have. A decision I would soon regret and will regret for the rest of my life. The first 20 issues of Beavis and Butt-Head Comic Book were in the top 100 books sold each month. In those days there were about 10,000 things to choose from.

In a market dominated by superheroes, I thought this was a great accomplishment. I had taken as my guiding light, the work of Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder the two brilliant geniuses who had been the driving creative forces in early Mad Magazine. I had been a devotee of early Mad Magazine as a child growing up in the 1950’s. I understood juvenile humor very was as I had been one of those people who easily managed to keep his inner child alive. My inner child is permanently 12. That suited me well for the project.

Along with Mike Lackey, who wrote the first five issues, I traveled around the US meeting people and generally being treated like someone special. I must say, it was great to work on something which was so popular and well-received. I was beginning to think I could do anything when they called and cancelled the book.

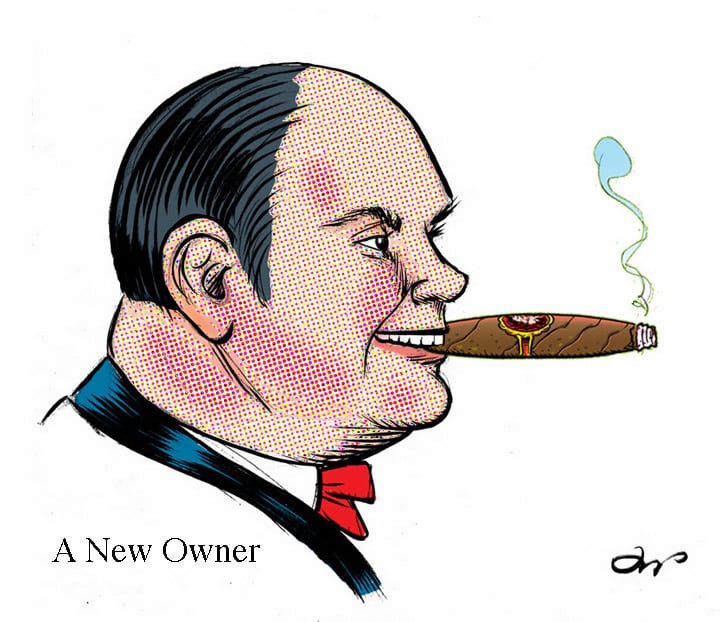

Marvel had changed hands and the new owner was not particularly interested in the publishing part of the business and certainly not interested in paying people like me good money to draw comic books which he did not even control the rights to. After almost 20 years at Marvel, I was out of work. My income dropped from about $150,000 year to next to nothing.

Marvel had changed hands and the new owner was not particularly interested in the publishing part of the business and certainly not interested in paying people like me good money to draw comic books which he did not even control the rights to. After almost 20 years at Marvel, I was out of work. My income dropped from about $150,000 year to next to nothing.

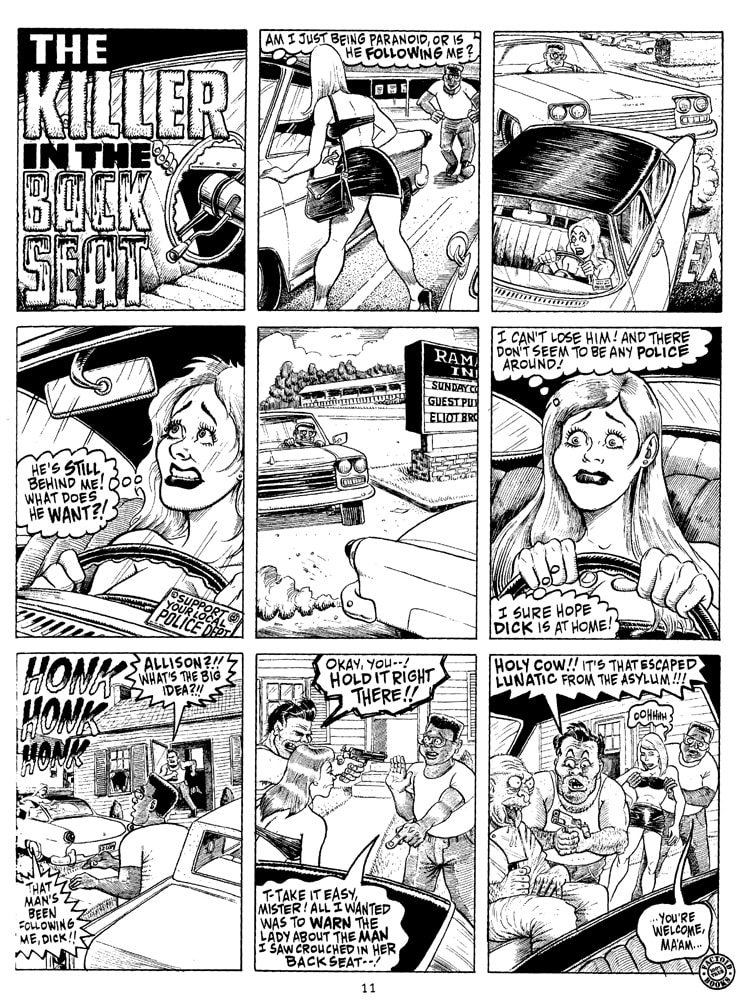

I did illustrate a few dozen pages for DC Comics Big Book Series at half my normal rate. The pages were double size and took a long time to draw. One story for “The Big Book of Hoaxes” featured a multi-page story in which two con men conspired to have people invest money in a scheme to saw Manhattan in half. I began to wonder which was more difficult—sawing Manhattan in half—or drawing that story. Another story from that time was “Sadie The Goat and Her Pirate Gang” These were fun and challenging assignments but they took weeks and I couldn’t make any money doing them. Not that I didn’t try. Meanwhile, Marvel never called me again.

I did illustrate a few dozen pages for DC Comics Big Book Series at half my normal rate. The pages were double size and took a long time to draw. One story for “The Big Book of Hoaxes” featured a multi-page story in which two con men conspired to have people invest money in a scheme to saw Manhattan in half. I began to wonder which was more difficult—sawing Manhattan in half—or drawing that story. Another story from that time was “Sadie The Goat and Her Pirate Gang” These were fun and challenging assignments but they took weeks and I couldn’t make any money doing them. Not that I didn’t try. Meanwhile, Marvel never called me again.

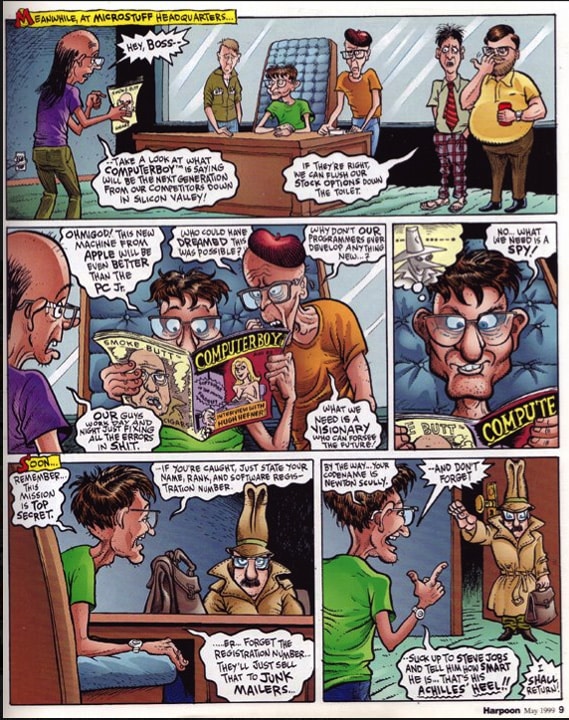

Just when I was really starting to get worried, from out of the blue I was contacted by a magazine publisher in California. He was a successful publisher of magazines and a good writer with a fine sense of humor and had always had it in his mind to publish a humor magazine. Now he had the money to make his dream come true. Thus was born Harpoon Magazine—a magazine of political satire. I don’t know where he saw my work but I was delighted to be working for him. My first story was “Frankengates” a long saga poking fun at Bill Gates and Microsoft and the various people who were pioneers in the computer industry. I did stories about The Monica Lewinsky Scandal and the O. J. Simpson trial. He paid me what I asked for and the magazine was in full color and had excellent production values. They carried the magazine at Hudson News in Penn Station. The problem was, I think, that it was impossible for any writer to top the absurdity of reality and those real-life situations. After a year or two of losing a small fortune, he pulled the plug. I have to hand it to him for trying, though. In the meantime computers came in big time and it became apparent that I was going to have to learn how to use one. I was immediately struck by how much the process of coloring would be improved.

I thought I would go into illustration. I contacted an old friend– a very successful illustrator. He told me I had picked the absolute worst time in the history of illustration to try and break into the business. Being one who has been too easily discouraged in the past, I produced a large color postcard with dozens of sample images on it and mailed it to a number of ad agencies and artists reps. Nothing came from it except one very nice rep told me she liked my work but was having trouble keeping her regular artists busy. It was discouraging to say the least.

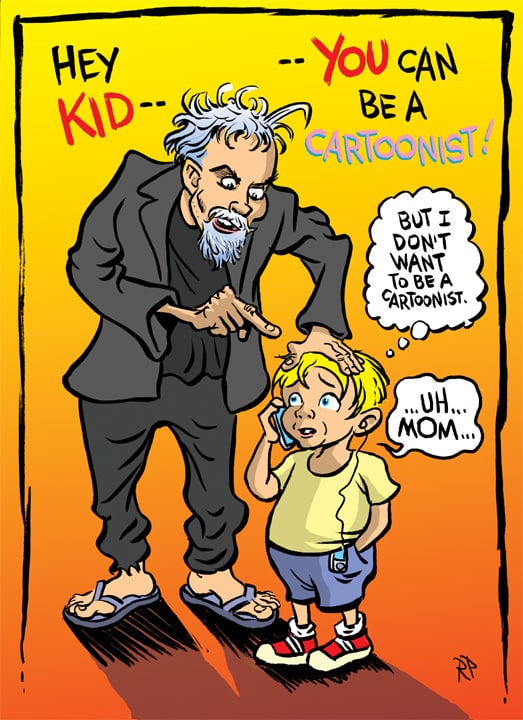

Along about this time, I was asked by my son’s kindergarten teacher if I would come and talk to the kids about my work. Not having anything else to do that day, of course I agreed. I discovered something wonderful. There was a part of me I had forgotten existed. I had first sensed it when, as an army officer stationed near a remote town in Utah in 1968, I had given a Fourth of July address to a small group of Mormons on what it means to be an American. That day I discovered that I was part carnival barker and part evangelist preacher and I liked the sound of my own voice. Anyway, the kids in my son’s kindergarten class seemed to like what I had to say and when I demonstrated a little drawing on a pad of paper they seemed mesmerized. The teacher soon had me teaching in the After-School programs of several elementary and middle schools in my area of New Jersey.

I think I was good at it. I had experience and passion about the subject and amazed myself with the funny things I said and did. I had always liked children and they seemed to like me, too. In the beginning I thought I was doing them a favor but soon realized that I was getting more from the experience than they were. Whereas before, during the time that I was working full-time in comics, I relied on my innate talent and my own intuition to guide me, after talking to the kids, I began to realize that there were good reasons why some things worked and others didn’t. If you have to explain something to someone else, it makes you think of it in a way that you hadn’t thought of it before.

I think I was good at it. I had experience and passion about the subject and amazed myself with the funny things I said and did. I had always liked children and they seemed to like me, too. In the beginning I thought I was doing them a favor but soon realized that I was getting more from the experience than they were. Whereas before, during the time that I was working full-time in comics, I relied on my innate talent and my own intuition to guide me, after talking to the kids, I began to realize that there were good reasons why some things worked and others didn’t. If you have to explain something to someone else, it makes you think of it in a way that you hadn’t thought of it before.

I began to really understand drawing, storytelling, and combining words and pictures to tell a story and that I could be very helpful in imparting those ideas to others. I began to see that I might be able to make a difference in some young person’s life when I saw the look on the face of a little boy from a very difficult background who was very quiet and reserved. I showed him how to draw a couple of facial expressions and suddenly his face lit up. It was like someone had given him something wonderful and no one could ever take it away from him. I’ll never forget that image in my mind. I kept this up for about 7 or 8 years.

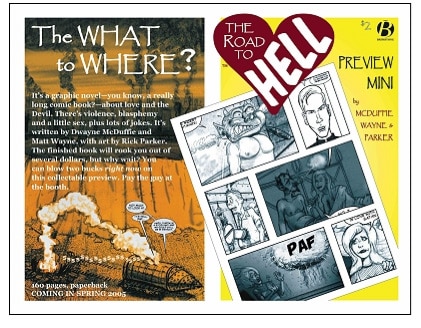

In 2004, I received a call from the late Dwayne McDuffie who asked me to illustrate a graphic novel that he was developing for Hollywood along with Matt S. Wayne. It was called The Road To Hell. It took me a year to do the 164 pages. There was some good drawing in there. Dwayne said it was “stunning”. I’m not sure what he meant by that, but he had previously let me know what he thought of my cartooning, so I guess he liked it.

In 2005, we began to open up our home one day per year to the public as part of what is called The Artists’s Studio Tour. I felt like a minor celebrity in our little town. Kids would see me on the street and yell out, “Hey, Mr. Parker!” or I would meet an adult at a yard sale or at some local event and they would already have heard about me. I started taking a few private students whose parents had been looking for someone to mentor their gifted children. I continued to learn as much from them as they did from me.

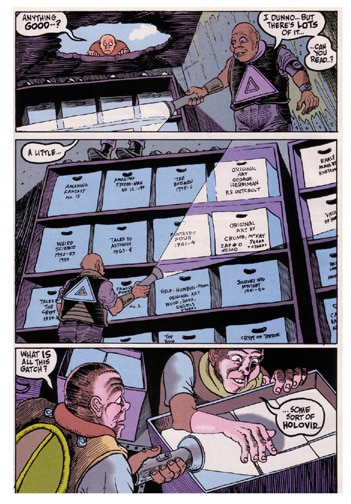

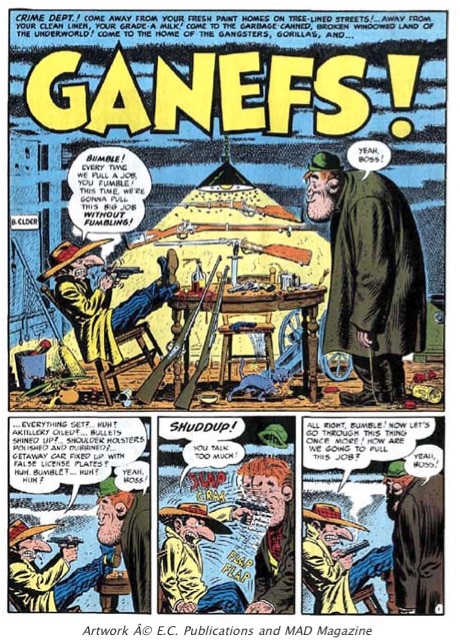

In 2007, just when I thought I would never work in comics again , my old editor and friend, Jim Salicrup called and said his company was bringing back Tales From The Crypt and would I like to draw the Introductory Pages featuring the Crypt Keeper, The Vault Keeper and The Old Witch? It was like being saved from a desert island.

Of course I said yes. In a way it was the perfect assignment for me as I remember being strangely fascinated by the Crypt Keeper and his long white hair, as I read an old EC Comic book at the barbershop while I waited my turn for a haircut fifty years earlier. Also the characters had been drawn beautifully by one of my favorite artists as a child, the great Jack Davis, whose work had inspired me to want to be an artist, myself. Alas, the remake of Tales From The Crypt never really caught on with the new generation of comics readers the way Jim had hoped. The younger ones had never heard of it and the older ones seemed unhappy at Jim’s attempt to bring the Crypt keeper into the modern age by giving him a laptop and cell phone. I thought it was funny as Hell and wanted to do the entire book—not just the intro pages!

Rejuvenated, I spent the next year writing and drawing the first work of any length I have ever both written and drawn. I called Deadboy, and it’s somewhere in between The Wizard of Oz and Night of The Living Dead. It’s a print on demand book and also available as an ebook. It went largely unnoticed. But I learned a lot from the experience.

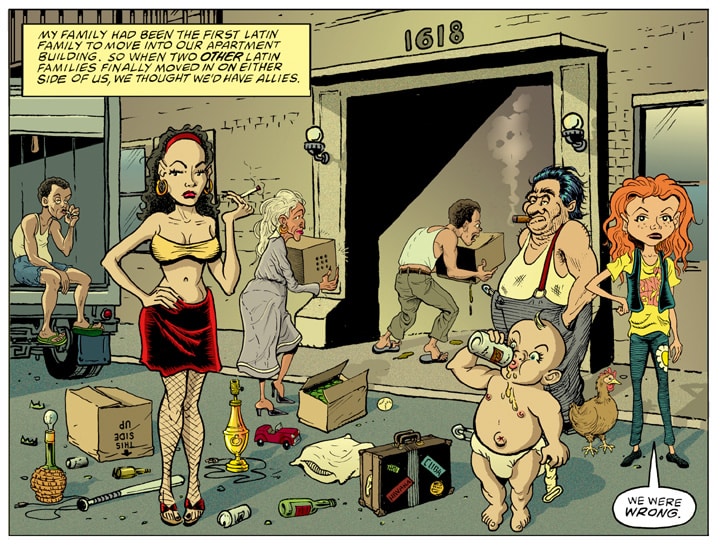

In late 2008, Dean Haspiel asked me to illustrate an 8 page story written by a young writer. Her story had been picked by Harvey Pekar as the winner in a contest. Her prize was that her story would be illustrated by a professional cartoonist. I said I’d do it. Dean apologized as he told me they could only pay $85. I said that’s all right. I thought he meant per page! I worked on it for three weeks. Dean loved it. Imagine my embarrassment when he called to tell me he’d received my bill for $680. He told me it was only $85 for the entire job! I didn’t realize it but I’d soon be working for Harvey Pekar for free—along with three other artists and an editor.

In late 2008, Dean Haspiel asked me to illustrate an 8 page story written by a young writer. Her story had been picked by Harvey Pekar as the winner in a contest. Her prize was that her story would be illustrated by a professional cartoonist. I said I’d do it. Dean apologized as he told me they could only pay $85. I said that’s all right. I thought he meant per page! I worked on it for three weeks. Dean loved it. Imagine my embarrassment when he called to tell me he’d received my bill for $680. He told me it was only $85 for the entire job! I didn’t realize it but I’d soon be working for Harvey Pekar for free—along with three other artists and an editor.

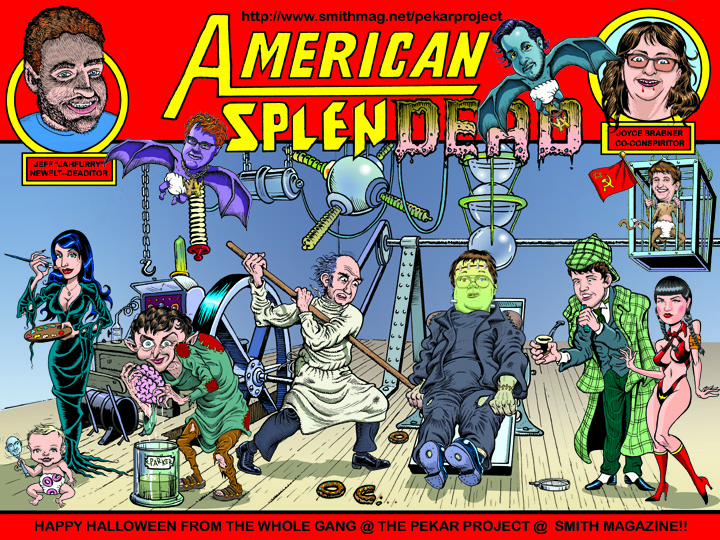

2009, was Our Pekar Year. I had long been an admirer of his autobiographical work and secretly harbored a desire to be one of his artists. I had been a little jealous when Dean got the job to do a book with him for DC. But Harvey picked Dean and Dino! Did a great job. As one of the four artists on The Pekar Project, Harvey would dictate stories to us on the phone and we would draw them and send them in to be put on the web. Harvey was interesting as Hell and things got really interesting when I drove my car to Cleveland along with the project Editor, Jeff Newelt, Brian Heater of PC Magazine and the comics blog, The Daily Crosshatch and another fellow who was going to interview Harvey.

We celebrated his 70th and final birthday at an art gallery featuring our drawings of his stories which was held in an old building which had been a donut shop he frequented as a child. Harvey and his wife, Joyce Brabner stayed at the opening for four hours. It was a blast. I watched them walk away from the gallery that night and walk slowly out of sight disappearing into the Cleveland night like characters in one of his stories. Harvey died unexpectedly the next year, but working with him was a dream come true and an honor and a privilege. A fascinating writer and man.

We celebrated his 70th and final birthday at an art gallery featuring our drawings of his stories which was held in an old building which had been a donut shop he frequented as a child. Harvey and his wife, Joyce Brabner stayed at the opening for four hours. It was a blast. I watched them walk away from the gallery that night and walk slowly out of sight disappearing into the Cleveland night like characters in one of his stories. Harvey died unexpectedly the next year, but working with him was a dream come true and an honor and a privilege. A fascinating writer and man.

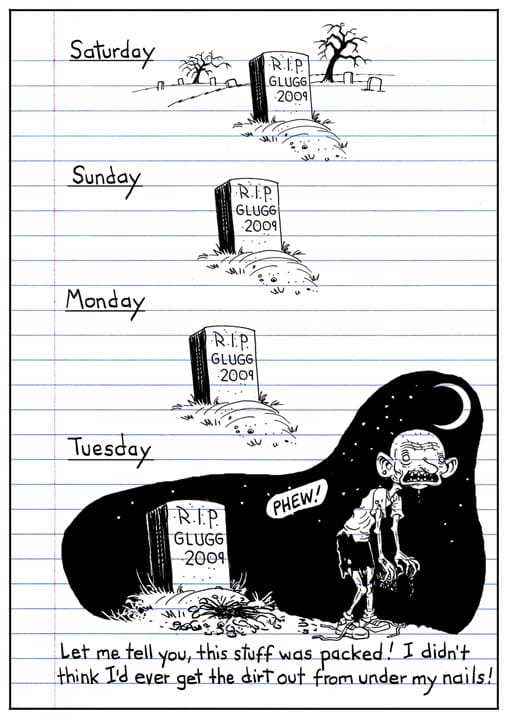

Earlier in 2009, Jim had teamed me up with writer, Stefan Petrucha, and we did a spoof of Diary of a Wimpy Kid. Ours was called Diary of a Stinky Dead Kid. It was a hit and based on that success Jim was determined to do parodies of other popular properties.

Earlier in 2009, Jim had teamed me up with writer, Stefan Petrucha, and we did a spoof of Diary of a Wimpy Kid. Ours was called Diary of a Stinky Dead Kid. It was a hit and based on that success Jim was determined to do parodies of other popular properties.

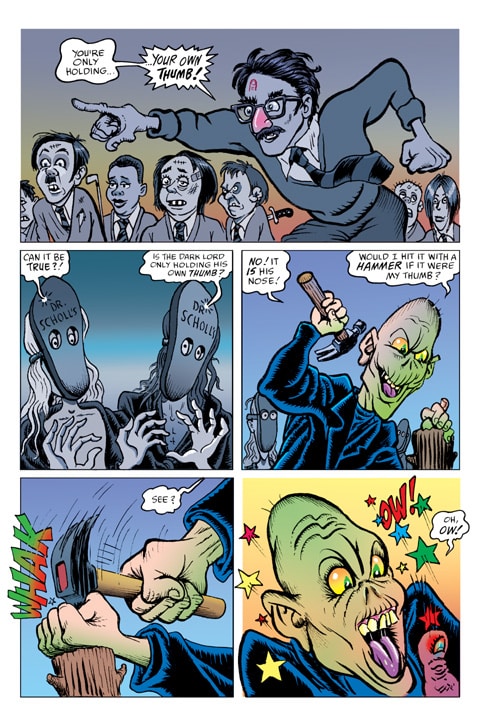

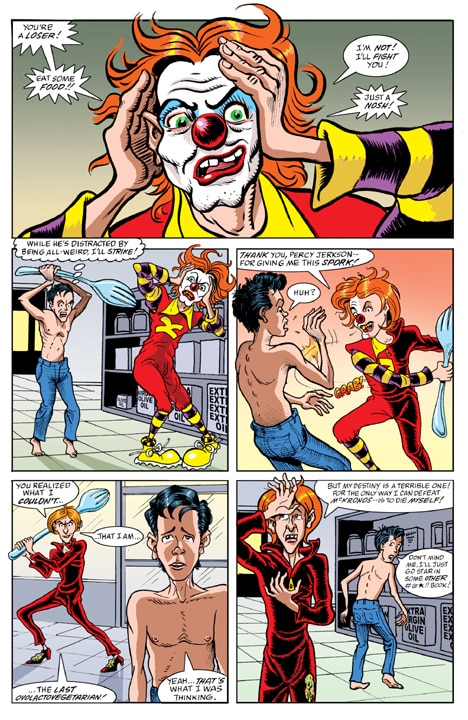

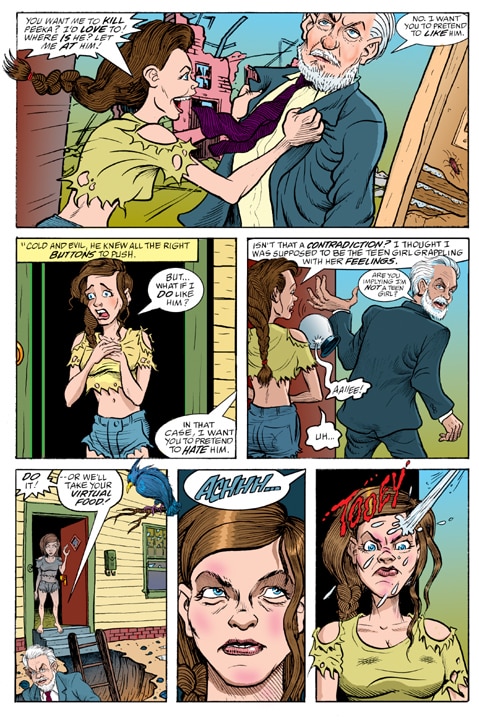

Working with Stefan Petrucha and with Jim as our editor, we produced 50 page full color Mad Magazine-style parodies entitled, “Harry Potty and The Deathly Boring”,

Working with Stefan Petrucha and with Jim as our editor, we produced 50 page full color Mad Magazine-style parodies entitled, “Harry Potty and The Deathly Boring”,

“Breaking Down” (a parody of twilight)

“Percy Jerkson and The Ovolactovegetarians”

“The Hunger Pains”

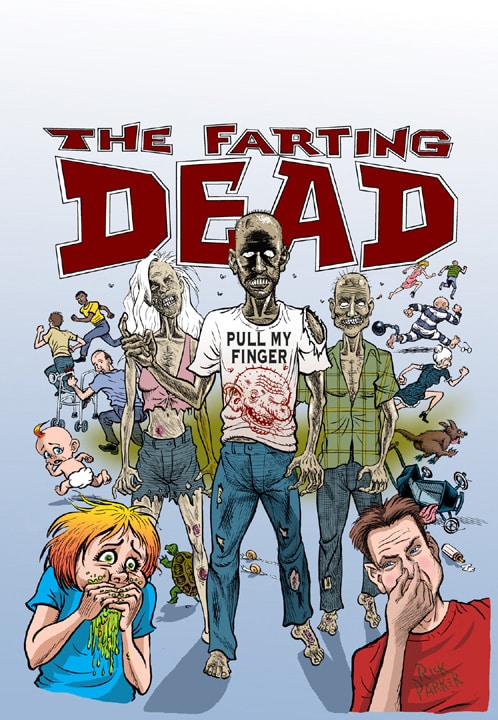

And my current project: “The Farting Dead”.

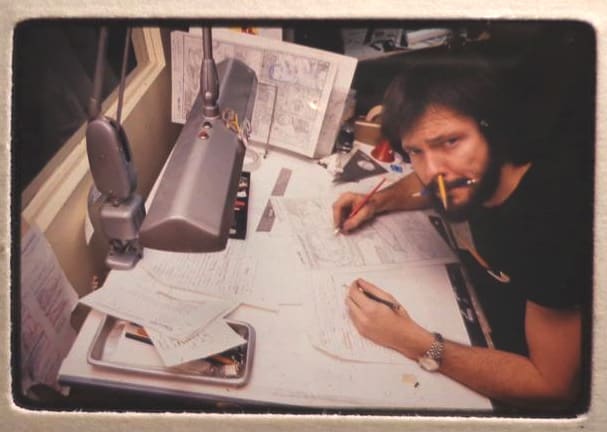

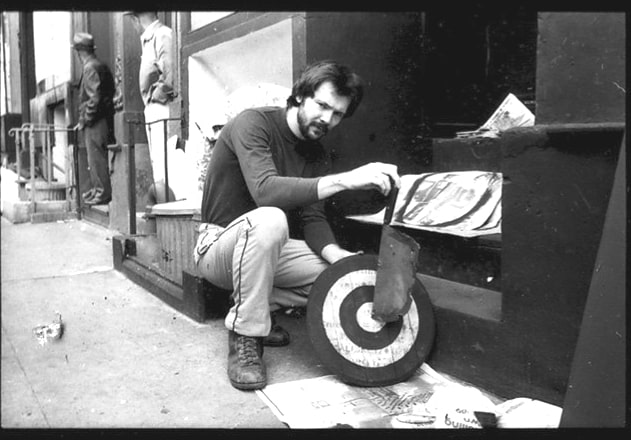

Rick Parker drawing in New York City, 1975

THE MILLION DOLLAR OFFER:

What you will be buying is the bulk of my lifetime’s work comprising several thousands of individual items including sketches, drawings, paintings, three-dimensional objects, photographs, Polaroid photographs, prints, collage, lithographs, mixed media construction, cartoons, comics pages, comic strips, multiples, collectible one-of-a-kind novelty items. It would take a long time do do an actual inventory of the entire collection.

I would be happy to answer individual questions in a general way. Anyone who is seriously interested would be allowed to come and see it for themselves. There is a great deal of work, both published and unpublished. I would like to emphasize that it’s a quality body of work. The collector who buys this collection would not just be getting a quantity of work, but a high-quality quantity of work!

For Media Inquiries, or if are a serious collector, you can contact Rick Parker here:

rickparkerart@gmail.com

Leave a comment