San Francisco, CA – Thursday, September 4, 2014

San Francisco, CA – Thursday, September 4, 2014

In June, New York-based artist Vanessa Albury gave an exclusive interview to Artiholics on the eve before her journey through the Arctic Circle. Along with 26 other residents, Albury took part of the Summer 2014 Arctic Circle Residency. Aaron O’Connor, who leads this program, directed a diligent crew that housed, fed, and safe-guarded the residents as they all worked on individual and collaborative research in the Arctic environment. This program brings artists, writers, musicians, educators, and scientists together to study one of the coldest, harshest regions of the world (-10 degrees Celsius). In total, the residents visited 18 landings.

Our report on this residency continues, first, by reviewing Albury’s unique documentation of the journey (a few images come from the program itself). In the above photo, Albury captured a star-shaped sun with strong beams of light high above the horizon after midnight. For 17 days in the Arctic, no nighttime sky appeared, nor stars, or sunsets. Everyone worked in sunshine and then hours later slept in its bright energy.

View of the Antigua, Photo courtesy of the Arctic Circle Residency Program

In the photo above, we see the temporary home for the residents–the Antigua, a 152-foot Barkentine sailing ship equipped with 3 masts. Furnished with cabin space, a kitchen, deck, and a communal salon, the Antigua presented the safest arena for the travelers to bond and discuss projects. Albury credits O’Connor and the guides Theres Arulf, Sara Orstadius, and Sarah Gerats (she is also a performance artist), as the masterminds behind the Antigua’s daily activities. With what seemed like innate finesse, the team juggled the needs of each resident on any and every task or equipment necessary for the multifarious projects. For Albury, they located landings close to glaciers and helped arrange portable power sources for her bulky projector. Other projects required similarly specific considerations. The team communicated with everyone tirelessly and effectively for each daily expedition. Above all, O’Connor, the guides, and the crew kept the residents safe.

Safety became a major concept keenly felt and then explored by some residents like Albury. During the travels, many participants felt awakened to the high degree of precaution constantly surrounding them. During hikes through icy terrain, the three guides doubled as polar bear guards and would scout the path of the expedition. They formed safety zones encompassing 300 to 400 meters at the widest point, in which the residents could work on projects. While traveling, the residents walked in a line or tight group, sometimes with only one guard. Albury fondly describes the polar bear guides as “amazing, rifle-totting, adventurous women.” If any polar bears appeared, entire hikes could be redirected or even aborted. Thanks to a presentation on polar bears by one of the guides, Sara Oristadius, the participants came to understand that “polar bears are fearless, curious and ferocious.”

On deck and anywhere close to the edge of water, residents had to be aware of the immediate doom resulting from a simple slip. Man-overboard in the Arctic does not resemble Man-overboard in warmer seas. According to the captain of the Antigua, in the waters around Svalbard, Norway (where the journey began) you would not die due to hypothermia, exactly. Before that, your layers of heavy clothing would pull you down into endless depths. There’s just no way to keep afloat without a lifesaver. On top of that, if the ship is sailing, it would be very difficult for any crew member to keep an eye on a small head bobbing in water. Closer north, any fall into the water could result in death from hypothermia. On land, danger comes from above. The explorers kept a minimum distance of 200 meters from any glacier to avoid sudden calving, the deadly splintering of heavy or sharp crashing ice from the tops of glaciers.

Photo of Vanessa Albury working with her pinhole camera during one of the landings in the Arctic Circle. Courtesy of the artist.

However hazardous the expedition felt, the members of the Summer 2014 Residency all returned safely. They may have joked about Scurvy, hoarding the limited supplies of chocolate, and other jests emanating from paranoia, but the group never stopped looking out for one another. Albury found herself in deep conversation with the writer and co-resident, Susan Rogers on this sensitive topic. Rogers talked about the precautions taken for safety, i.e. the strict boundaries to protect against polar bears and the rules aboard the ship. Albury could relate, thinking of the ships’s rails. She also contemplated the “edges of life and living,” while recalling tales of whalers and early explorers, many who did not return from these Arctic expeditions.

Albury thinks of how those crucial moments come from the simplest places. It could have been just one small item left behind that might have made all the difference for those explorers who perished. An entire journey could be ruined, or an entire life might splinter and end from simply forgetting to think about the entire scope of needs for an expedition. While sharing these thoughts with Rogers, Albury noted that this interest may resurface in her future work, stating also that, “the best gift a residency can give an artist is fodder for new thoughts and new ideas.”

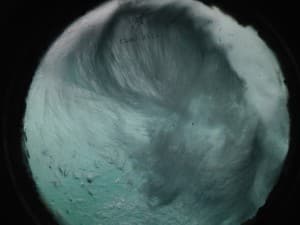

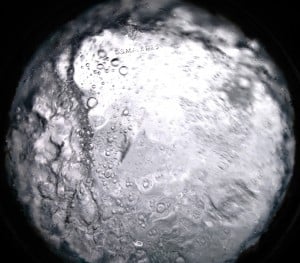

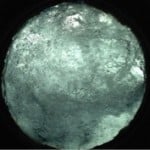

Another series of photos come from capturing the different scenes splashing round and round the porthole (11” diameter) in Albury’s cabin. All residents stayed in similar rooms during this two-week expedition. Sometimes, a view of the icy landscape and edges of shoreline are caught in this round window. More often, bubbly blue, clear, and green waters completely invade Albury’s round window. Leads one to wonder if the ocean is not actually one large glass of soda.

Another series of photos come from capturing the different scenes splashing round and round the porthole (11” diameter) in Albury’s cabin. All residents stayed in similar rooms during this two-week expedition. Sometimes, a view of the icy landscape and edges of shoreline are caught in this round window. More often, bubbly blue, clear, and green waters completely invade Albury’s round window. Leads one to wonder if the ocean is not actually one large glass of soda.

I am reminded of stargazing, and how surely hypnotic those porthole scenes might have appeared to someone resting from long hikes through snow. Deeply, I enjoy those moments when art objects resemble or rather, cause a sense of star-gazing in me, a relaxed state where one dreams quietly, not even noticing that you are—as they say, in the moment.

This series of pictures feels intimate, as the images come from the artist’s private quarters, which is a part of the journey that shouldn’t be forgotten. The porthole views remind us that we cannot leave the vessel out of this story. It played a very real and present part of the exploration and residency. Not everything took place outside. Albury noted that this was certainly true for the residency’s writers. While many joined in on the daily hikes, the writers often stayed in for hours to practice their craft.

Albury’s craft also involves developing her film, when possible. In past residencies and travels, she has been known to scope out the right closet or bathroom to turn into a temporary dark room, which is what she also did aboard the Antigua. Though she brought several heavy pieces of equipment, Albury did not pack an enlarger. The type of developing she worked on involved chemicals and exposed film. A dark room on a ship works well, only when the ship is not moving, or when her neighbor does not need his shower.

Photo courtesy of Vanessa Albury.

One of the more relaxed characters in Vanessa’s photos includes a portly “Red-Bearded Seal”. The name might be related to the patch of rusty bronze color of the fur or skin on his face, but I’ve seen humans with more red and beard than this fellow. Place those terms, “red-bearded seal” into an Image Google Search, and you will come across a few male homo sapiens. Lying on his left side, Albury captured the seal softly blinking his coal lump eyes as he allowed the group to come as close as one meter. The residents and their guards did spot polar bears during two expeditions—a single bear the first time, and then a mother and 2 cubs the second time. Four bears in total made a record for any ship traveling during those 2 weeks. No one was allowed to get as close to a polar bear as Albury got to the blinking seal. Almost immediately, when the first bear dived into water, the group had to quickly return to the ship. Polar bears swim fast, act stealthily, and are skilled at hunting. During the second sighting, the traveling group only redirected the path of their hike.

Near the end of the residency, Albury documented one of the final hikes around the curved path in this picture. Note the dark grey stone and the blue ice covering the curved rim. Layers and layers of ice create the most fascinating shades of translucent blue, frosty on some edges, other times jagged, or fragmented. In another shot of the terrain, Albury captures blocky rocks that have the grey color of elephants.

After hikes like this (some lasted up to three hours), the travelers came home to a warm Antigua set with healthy, filling meals. Albury recalls a “lovely chef” who catered to all the food allergies from the group. The artist remembers abundant servings of pudding (with almost every meal!), dishes with fish, pork, chicken, pastas, and European fashioned salads (cucumber, tomatoes, corn, and onions, notably salads made without leafy-greens, which Albury missed).

Most of the images reviewed above come from the artist’s documentation of the journey, but this does not describe her artwork very well. We should not think of Albury as a photographer. During our 2nd interview, we talked about how often people refer to her as a photographer. It’s an easy mistake. After all, the artist did return from her past two residencies with hundreds of rolls of film. However, the goals between this artist using photo-based processes and a photojournalist, for example, vary widely.

Net Diptych (Bodøgaard XVI & XVII). Vanessa Albury created this Cyanotype print using nets and rope. 2014

Albury’s work centers on how light behaves, the mood of it, and our response to these images. They often carry abstract forms that she experiments with, often incorporating other sound or performance-like elements from projectors. The different ranges of cameras available to us, the kind that have been replaced by a lot of digital technology still interest Albury. Holga cameras (her favorite), pinhole photos, or projectors are all devices that allow her a range of ways to experiment with light. The different film speeds and shutter capabilities from these cameras give the artist many options, almost like the varying colors on a painting palate. When looking at her work, I do feel as though I am looking at paintings.

Documentation of Waves (The Impossibility of Distinction for Mr. Palomar. Projectors, recorded sound. Vanessa Albury, 2024

To better illustrate Albury’s use of photography, we can refer to the show she participated in right after the Arctic circle Residency. In an exhibit named The Dream Time curated by Rachel Mason at Trans Pecos in Queens, Albury showed a projection piece to a sitting audience. She projected 48” x 48” black and white 35 mm slides depicting a dozen different images. The pictures move in an irregular pattern. Some repeat more than other, so that viewers cannot spot a pattern. Simultaneously, the audience heard clicking projector noises that ticked against the sound of Albury’s heartbeats while she settled into a rest mode. By making those components work together, Albury aligned “The delicate human body to the corporeal nature of waves.” The artist also found herself incorporating the meditation in Italio Calvino’s essay “Reading a Wave.” In this piece, one of Calvino’s most known characters named Mr. Palomar contemplates the colors, constant movement, and motley body that waves take on—how they never cease to change. Can Mr. Palomar possibly observe just one wave without the legions of others? Like snowflakes, have any two waves ever existed with complete a likeness? The piece is documented in the image above, and it is titled Waves (The Impossibility of Distinction for Mr. Palomar).

To echo an earlier conversation from our first interview, Albury says that “Photos are objects. We tend to think of them as these windows into the world, but they are not. They are objects,” and the artist treats them as such. Instead of seeing photos as just images, Albury considers the entire scope of factors that come from taking a photograph – the processing, the act of capturing light phenomena, or the site specificity of projections. She focuses on these elements can be recombined with other elements, like sound, and result in these exploratory ways of drawing in viewers. In pieces like the Waves (…Mr. Palomar) the key concepts come from mixing sound with images. Another future project will bring fire to the development process. Albury found inspiration from the duality of heat (there is some with, ie the midnight sun) and the obvious cold elements of the Arctic. Spotting that phenomena unique to the polar environment inspired this unusual photo process. She plans to burn an image while developing it. We’ll have to wait to see the end results of that creation/destruction process. Call the items resulting from this Fire-Photo-Bath, Albury’s artifacts. We may not be there for the ritual, but can see the end results and observe how they contrast and work together.

Net (Bodøgaard XXIII), Vanessa Albury, Cyanotype Print, 2014

The Arctic environment kept Albury from completing some of her work. For one project, the artist intended to project images of decaying buildings upon glaciers. She wanted to connect failing or neglected man-made buildings with these majestic formations of nature that are also sadly breaking down. Her idea work intuitively found a connection between the environments, for they both seem “vulnerable and on the edge of collapse” wrote the artist in an email exchange. The decay of both formations originate from man’s actions. Those projections would cover the glaciers and easily be removed without a trace left in the surrounding environment. In order to project, Albury sought glacial caves where her projections could fully appear in the shadows. However, she could not safely get close enough to the caves due to the dangerous summer calving. Still, Albury called these “beautiful failures.” At the time, her co-resident, Jess Perlitz, who is a sculptor and performance artist, offered to create a large projection screen out of snow. After Perilitz fashioned the screen, Albury said it looked like a tiny white theater. In the end, the power source still did not allow Albury to use the projector properly. That day, Perlitz also constructed a fort made of cinder block-sized snow bricks, and later the residents “had a house, a theater, some industry in the form of a snow brick mining site and a graveyard, all in a day’s work and through Perlitz’ practice,” wrote Albury in an email.

Photo courtesy of Vanessa Albury

In one instance, Albury found a way to project onto cave walls. The large part of this projection project still remains to be continued. Without the least bit of dissatisfaction, Albury said she intends to return to the Arctic terrain, during one of the seasons outside of the Summer Solstice. This was a fantastic first run for future work. Partly, the wanderlust now ingrained in this artist must have been talking. In our interview, we spoke about the places where art making comes from. For many, it involves stationary hours in the studio. For this photo-based artist, travel to distant lands will influence many of Albury’s concepts. So she’ll need to travel and understand how to do it. As someone who has never gone camping, I asked Albury how easy or hard would it be to make a trip to the Arctic Circle. For her, the path would take lots of work, but thanks to this residency, it seems clear to Albury how she could make that trip happen.

End Notes:

Out of 27 residents, 7 came from foreign countries. The rest are U.S. citizens, like Albury. The Summer 2014 group had an unusually high number of females to males, however, Albury says that past groups more often carried an even number of males to females. Everyone spoke English, including the crew and guards. Canada Goose gladly sponsored Vanessa’s travels by providing her special attire for -10 degree Celsius weather. The Arctic Circle Residency program ships 2 groups (about 30 people in each group) to the Arctic Circle every year.

Written By: Audrey Tran

Leave a comment